The Stories We Tell Ourselves: Reading Recovery and the MSV Myth

by Jeffery Williams

Every culture across time has developed a set of stories, tales, and myths that were designed to help explain the complexities of the world. Such lore is handed down across generations to explore how human strive for love, what happens when jealousy takes over, or to try to make sense of natural disasters or phenomena. These stories, usually orally presented and often borrowed from others, evolve and change over time, helping to bring the wisdom of the ages to those who have had less time to ponder or less experience to gather from to understand the complexity around us.

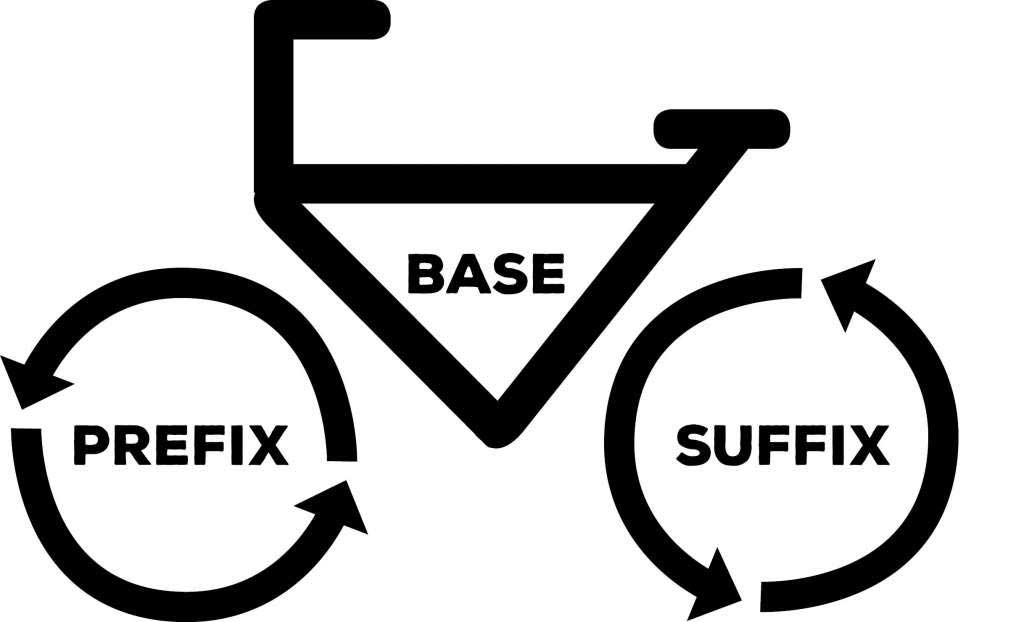

We, as a Reading Recovery community, have one such tale in the oft cited myth that there are three cues readers use, meaning, structure, and visual, or that Marie Clay herself created this theory and the corresponding three-circle depiction that is familiar to most teachers. Perhaps it originally was used to water down the complexity of the reading process for new teachers, in classrooms and in Reading Recovery, to make it easier to understand. The purpose of this blog is to explore what Clay actually said and to remind us that such myths, though they may have been purposefully utilized at one time, also need to be checked against reality and not just adhered to because it is a story we have heard before that must be true.

“Three Cueing Systems”

Though other researchers have pondered the proliferation of the three cueing systems model, the most notable and thorough pondering came from Marilyn Adams’ 1998 chapter called, The Three-Cueing System. In this piece, Adams examines the origins of the theory (finding that idea did not originate with Clay) and also discusses the pervasive misunderstanding that the three cues are not equal or that the visual system is somehow less important than meaning or structure. I agree that the view presented with the “three cueing systems” is limited for several reasons. Firstly, Clay did not advocate the idea that there are only three sources of information:

“According to the theory of reading behind these recovery procedures there are many sources of information in texts” (Clay, 2016). Furthermore, she did not advocate the use of any one source as the sole basis of reading or making a word attempt, stating: “Different kinds of information may be checked, one against another, to confirm a response or as a first step towards further searching.” A careful reading of this statement uncovers that one source may be a first step towards further searching and that searching would always involve a close look at letters and sounds.

According to Adams (1998), the notion that the reader constructs the meaning of the text as jointly determined by lexical, semantic, and syntactic constraints had been a theme of the reading literature since the late 1970s. She found that the problem was not with the three cueing systems schematic but with some interpretations that had become attached to it. For example, a common misinterpretation is that the position of graphophonic information in the Venn diagram with 3 circles as below the other two somehow diminishes the value and use of such information while reading. From a Reading Recovery perspective, we disagree with this interpretation and Clay spends an entire chapter on learning to look at print and states vociferously in the opening that:

Reading begins with looking and ends when you stop looking. Reading begins with passing information through the eyes to the brain. But the eyes do not just take a snapshot of the detail of print and transfer it to the brain,

- The child must learn to attend to some features of print,

- the child must learn to follow rules about direction,

- the child must attend to words in a line in a sequence, and

- the child must attend to letters in a word in left-to-right sequence.

(Clay, 2016, p. 46)

Although Reading Recovery teachers analyze daily running records using meaning, structure, and visual, our analyses go well beyond MSV as we closely examine the records to better understand students’ strengths, to identify teaching goals, and plan the next lesson. To learn how to do this, as Reading Recovery teachers, we take weekly graduate coursework for an entire year during initial training and continue our learning through ongoing annual professional development six times per year. The depth of this training and the ongoing nature of a university support system enables us to identify the complexity of student behaviors and plan precise teaching to support increasingly complex reading and writing that goes well beyond just MSV.

Teaching Phonemic Awareness and Phonics

Perhaps because of the myth of the three-cueing system, critics have often supposed that visual information is not emphasized or taught in Reading Recovery lessons. This is quite untrue and is supported by nearly four decades of empirical research which show Reading Recovery’s strong effects across all domains, including phonics, phonemic awareness, and comprehension. For more information on some of these studies, please see the What Works Clearinghouse website. Also, on the What Works website is a recent 2016 publication from IES, Foundational Skills to Support Reading for Understanding in Kindergarten Through 3rd Grade, with Barbara Foorman as the chief author. It was commissioned to present recommendations “…that educators can use to improve literacy skills in the early grades…based on the best available research, as well as the experience and expertise of the panel members” (Foorman et al., 2016, p. 1). Research from Reading Recovery is cited 117 times by the authors in support of the panel’s four recommendations. To demonstrate the alignment of some of Foorman’s key recommendations with typical Reading Recovery lessons, citations from Foorman (2016) and Clay (2016) are shown below:

| Foorman Recommendations | Foorman Citations | Clay Citations |

| Using Elkonin boxes in writing to develop phonemic awareness | pp. 24, 26, 27 | pp. 98, 100, 107 |

| Procedures for learning letter-sound relationships through segmentation | p. 19 | pp. 58, 98, 100, 106, 107, 173 |

| Procedures for using manipulatives such as magnetic letters for learning how words work | pp. 19, 24 | pp. 40, 58, 63, 68, 72, 91, 149, 151, 175 |

| Teaching breaking words by syllables | pp. 15, 16 | pp. 95, 107, 149, 173 |

| Teaching onset/rimes | pp. 15, 16, 19 | pp. 58, 107, 150, 153, 156, 160, 173 |

| Teaching meaningful parts | pp. 27 | pp. 73, 107, 152 |

| Teaching how to isolate and blend word parts smoothly | p. 24 | p. 96 |

| Using writing to help with analogies with spelling patterns | p. 26 | pp. 90, 105 |

| Within text blending by chunking or in smaller units within text | p. 23 | pp. 96, 144, 175 |

| Avoiding guessing strategies | p. 34 | pp. 48, 101, 118 |

| Reading connected text daily | pp. 1-3, 22, 28, 32 | pp. 20, 110-165 |

Interestingly, the Foorman document states, “When students encounter words that they find difficult to read, remind them to apply the decoding and word-recognition skills and strategies they have learned and to then reread the word in context … using prompts such as: ‘Look for parts you know.’ ‘Sound it out.’ ‘Check it! Does it make sense?’” (p. 34). These prompts are almost verbatim to Reading Recovery prompts (Clay, 2016) and seem to suggest that research favors using multiple sources of information to cross-check one against another and does not favor the use of any one source solely.

A recent document for parents from RRCNA (2019), outlines how phonemic awareness and letter/sound relationships are taught in Reading Recovery:

- Phonemic awareness is initially established with structured instruction during the writing component of the lesson.

- Letter identification is taught using multisensory approaches and reinforced throughout the series of lessons to ensure fast, accurate recognition and discrimination.

- Applying known letter sound associations and linking sound sequences to letter sequences is addressed in both reading and writing.

- All new learning is applied and observed/analyzed in reading and writing every day.

- Fast visual processing is supported as the child analyzes unknown words in stories by taking them apart on the run.

- Your child will develop the advanced analysis skills needed for decoding multisyllabic words and will profit from classroom word work and study.

- The teacher monitors your child’s daily progress in word analysis and re-teaches as needed. Many opportunities for applying new skills are provided daily across multiple reading and writing activities. (p. 3)

These references might clear up misunderstandings about Reading Recovery, particularly for those who think that Reading Recovery students are not taught phonics or phonemic awareness.

Value of Reading Connected Text

Reading Recovery’s daily use of connected, continuous text, where children cannot afford to rely on any one source of information entirely, is clearly an advantage and is supported by Foorman’s report on the research: “Having students read connected text daily, both with and without constructive feedback, facilitates the development of reading accuracy, fluency, and comprehension and should begin as soon as students can identify a few words” (p. 32). Two other recent publications—one from the International Literacy Association (ILA) and another from the International Dyslexia Association (IDA)—also offer suggestions that are supportive of the idea that reading continuous text daily, again because it demands that the reader not be able to rely solely on any one source of information, may be advantageous:

Students progress at a much faster rate in phonics when the bulk of instructional time is spent on applying the skills to authentic reading and writing experiences, rather than isolated skill-and-drill work. At least half of a phonics lesson should be devoted to application exercises. For students who are below level, the amount of reading during phonics instruction must be even greater. (Blevins, et al., p. 6)

And, in discussing the problem of “treatment resistant literacy difficulties” for students who have had a structured literacy approach and not shown evidence of success, IDA offers the following recommendation:

Another way to address this problem could involve placing a greater emphasis on text reading in intervention, which scientific investigators widely agree is an important aspect of intervention (e.g. Brady, 2011; Foorman et al., 2016; Kilpatrick, 2015), to help increase children’s exposure to real words. This last idea might be effective if done early, before decoders have accumulated the enormous gap in reading practice characteristic of older poor readers in the upper elementary grades and adolescence (Cunningham & Stanovich, 1998; Torgesen, 2004).” (International Dyslexia Association, 2019, p. 13)

Reading Recovery Research

While no single approach works for every child, Reading Recovery has the strongest evidence base of any of the 228 beginning reading programs reviewed by the U.S. Department of Education’s What Works Clearinghouse. Because of Reading Recovery’s impressive research base spanning decades, in 2010 the Department of Education provided $46 million to fund a 5-year scale up of Reading Recovery in schools across the U.S. In 2016, an independent research study of this scale-up was published by the Center for Policy Research in Education. The study was the largest randomized controlled trial “and one of the most ambitious and well-documented expansions of an instructional program in U.S. history” (May et al., 2016).

The results demonstrated Reading Recovery’s impressive effect sizes on comprehension and overall reading achievement. These effect sizes were replicated four years in a row and authors noted that “these are large relative to typical effect sizes found in educational evaluations. This benchmark suggests that the total standardized effect sizes…for Reading Recovery of 0.37, was 4.6 times greater than average for studies that use comparable outcome measures” (May et al., p. 42). This has been proven in both urban and rural settings, as well as with English learners. School districts invest in Reading Recovery training for teachers because of these documented successes for the past 35 years.

Myth or Reality?

The myth that Marie Clay was the origin of the three-cueing system model is certainly false as the readings of Clay demonstrate and as Adams confirmed. And, the myth that Reading Recovery does not teach phonics or phonemic awareness, because the visual system is somehow less important, is also false. So why then are these stories so closely linked to Reading Recovery? I know that I saw a diagram of the three-cuing systems in my training nearly two decades ago. I know that I have used a similar diagram when introducing running record analysis with classroom teachers. I never intended it to supplant the idea of complexity, but perhaps had forgotten the essence of Clay’s warning when she wrote, “If literacy teaching only brings a simple theory to a set of complex activities, then the learner has to bridge the gaps created by the theoretical simplification” (2015, p. 105). She was not only talking about children’s learning but our learning as well. When diagrams or explanations water-down the complexity, we run the risk of learners ‘bridging the gaps’ on their own—filling in what is unclear with their own thinking or ideas that were never intended and that may or may not be helpful. Clay believed that teachers wanted and needed exposure to the complexity of theory and research and once said, “…the challenge for me is to write those theoretical ideas for the academics and researchers but also for the teachers. I think they have a right to be able to read those in terms that they understand. This has been one of my particular challenges…” We must likewise refrain from over-simplifying the complexity of becoming literate with myths and stories for our explanations.

References

Adams, M. J. (1998). The three-cueing system. In J. Osborn & F. Lehr (Eds.), Literacy for all: Issues in teaching and learning (pp.73-99). New York: Guilford Press.

Clay, M. M. (2016). Literacy lessons designed for individuals (2nd ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Clay, M. M. (2015). Change Over Time in Children’s Literacy Development. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Foorman, B., Beyler, N., Borradaile, K., Coyne, M., Denton, C. A., Dimino, J., Furgeson, J., Hayes, L., Henke, J., Justice, L., Keating, B., Lewis, W., Sattar, S., Streke, A., Wagner, R., & Wissel, S. (2016). Foundational skills to support reading for understanding in kindergarten through 3rd grade (NCEE 2016-4008). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE), Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from the NCEE website: http://whatworks.ed.gov.

International Dyslexia Association (2019). Structured literacy: An introductory guide. Retrieved from the International Dyslexia Association website: https://dyslexiaida.org/structured-literacy-works-but-what-is-it-introducing-idas-new-structured-literacy-brief/

International Literacy Association. (2019). Meeting the challenges of early literacy phonics instruction [Literacy leadership brief]. Newark, DE: Blevins, et al. Retrieved from the International Literacy Association website: https://www.literacyworldwide.org/get-resources/position-statements

Reading Recovery Council of North America (2019). How Reading Recovery helps your child learn. Retrieved from the RRCNA website: https://readingrecovery.org/supporting-struggling-readers/

Jeffery Williams is a Reading Recovery Teacher Leader and K-12 Literacy Teacher Leader from Solon City Schools, Solon, OH.