Thank You, Reading Recovery Community!

Thanksgiving is a time for reflection, togetherness, and gratitude. This year, we’re thankful for every member of the Reading Recovery Community. Thank you for working tirelessly to help children learn to read.

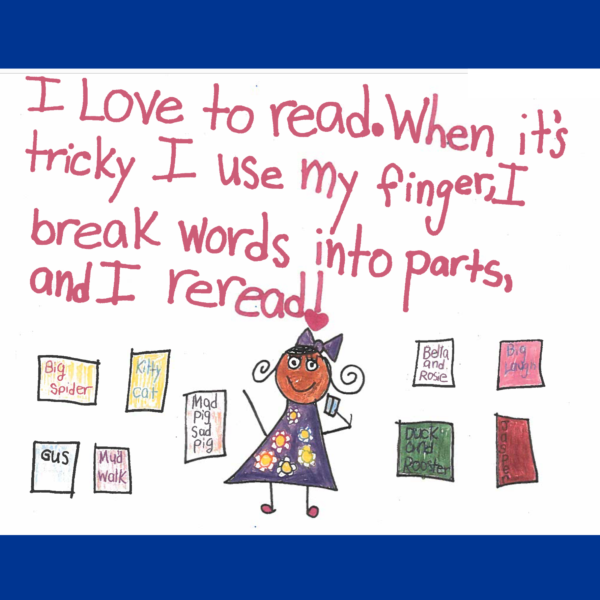

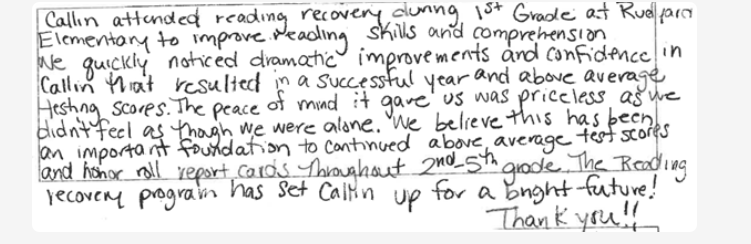

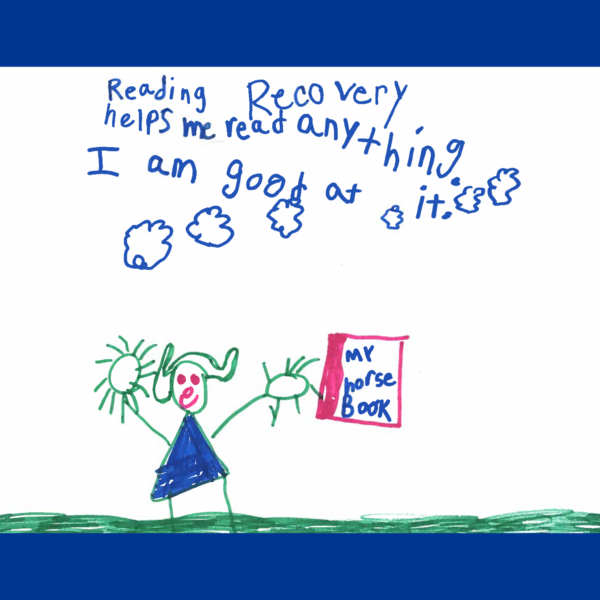

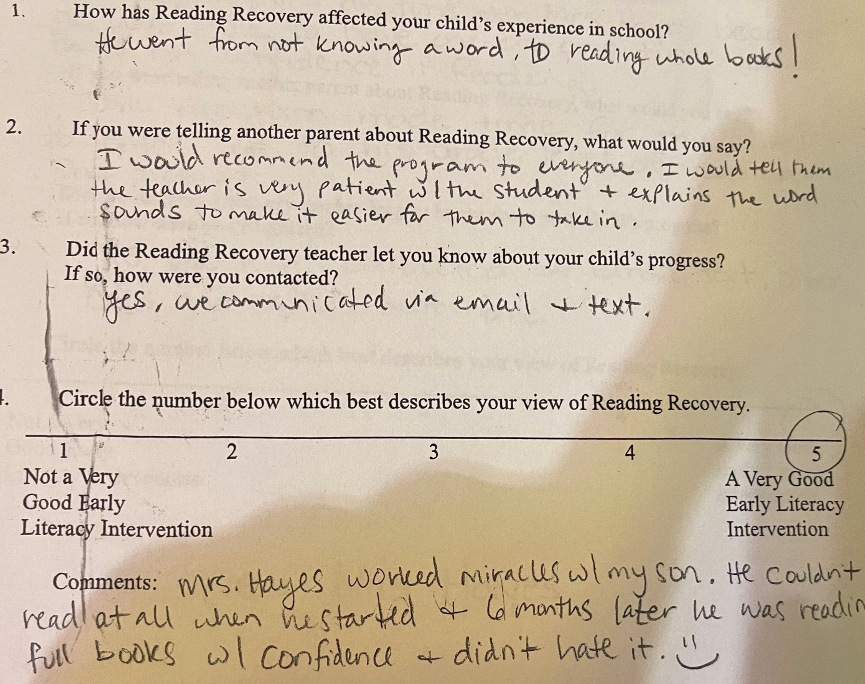

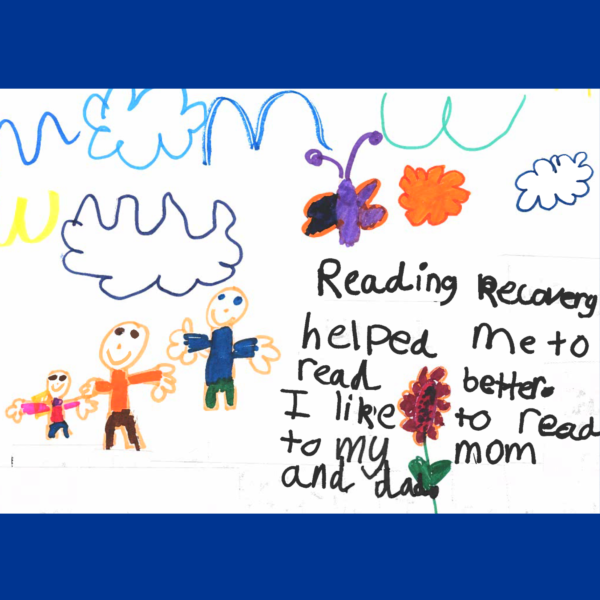

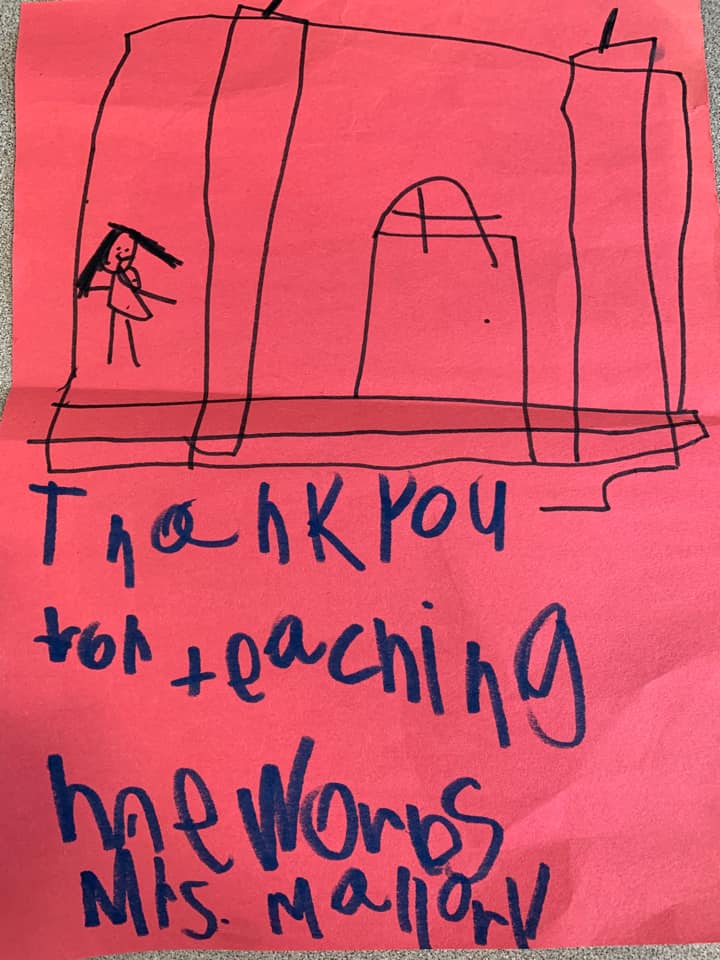

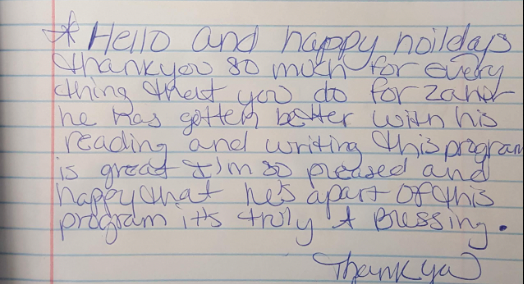

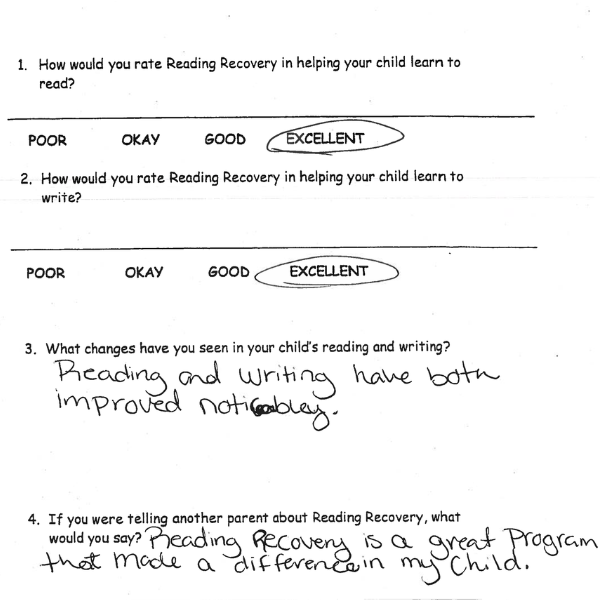

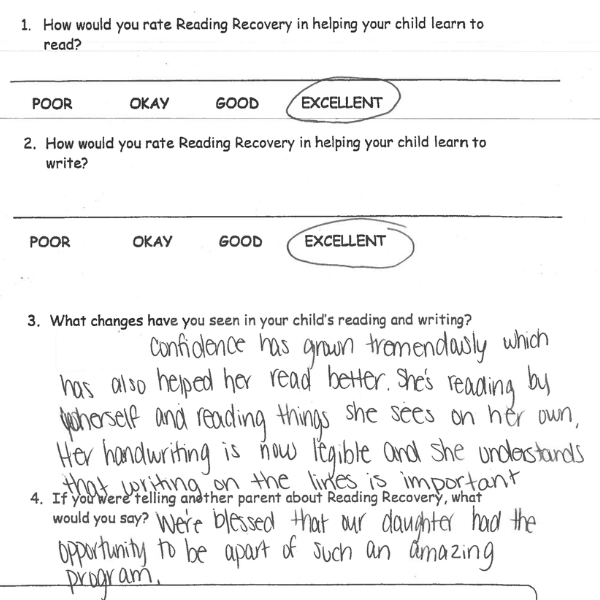

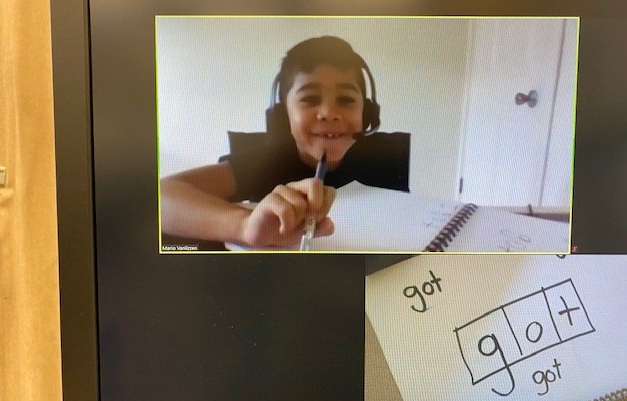

Browse our thank you note gallery below. Add a thank you note you received to the comment section in our community and social media and we’ll add it to this post! Bookmark this post for whenever you need a pick-me-up. Your commitment and passion is appreciated!

Children are resilient and what they bring to our classrooms, in person or virtually, needs to be acknowledged, valued, respected, and honored. I cannot help but think of Marie Clays’ words of wisdom that remind us that students take different paths to common outcomes and that is both okay and important to take into consideration in instruction. Cassi Clausen reminds us “Ask any child development expert, and they will tell you that children do not develop in a straight line. There are no average children. There are no standard children.”

Children are resilient and what they bring to our classrooms, in person or virtually, needs to be acknowledged, valued, respected, and honored. I cannot help but think of Marie Clays’ words of wisdom that remind us that students take different paths to common outcomes and that is both okay and important to take into consideration in instruction. Cassi Clausen reminds us “Ask any child development expert, and they will tell you that children do not develop in a straight line. There are no average children. There are no standard children.” I have some concern students will be set up for more learning loss if we treat students the same, think they ALL have a loss of learning and we teach to the floor and not the ceiling. As educators, we must have the mindset of acceleration, not remediation, value our student’s new knowledge and experiences, and fill in the gaps when necessary. As Marie Clay has stated in “Literacy Lessons” page 20, “Achieving acceleration is not easy but it must be constantly borne in mind.” Moving forward, ongoing keen observation, formative assessments, and differentiation will be more important than ever. And we must celebrate individual differences as assets. We approach student learning to start where each child is and take them as far as we can. During Mary Howard’s presentation at LitCon 2021, she challenged educators to think about interventions as opportunities throughout the entire school day, not as an isolated act or time. She also expressed interventions should not work in isolation but be connected to a comprehensive learning system. This vision for intervention would be inclusive for all students in need.

I have some concern students will be set up for more learning loss if we treat students the same, think they ALL have a loss of learning and we teach to the floor and not the ceiling. As educators, we must have the mindset of acceleration, not remediation, value our student’s new knowledge and experiences, and fill in the gaps when necessary. As Marie Clay has stated in “Literacy Lessons” page 20, “Achieving acceleration is not easy but it must be constantly borne in mind.” Moving forward, ongoing keen observation, formative assessments, and differentiation will be more important than ever. And we must celebrate individual differences as assets. We approach student learning to start where each child is and take them as far as we can. During Mary Howard’s presentation at LitCon 2021, she challenged educators to think about interventions as opportunities throughout the entire school day, not as an isolated act or time. She also expressed interventions should not work in isolation but be connected to a comprehensive learning system. This vision for intervention would be inclusive for all students in need.