‘Roaming Around the Known’ with an Adult Learner

by Regie Routman

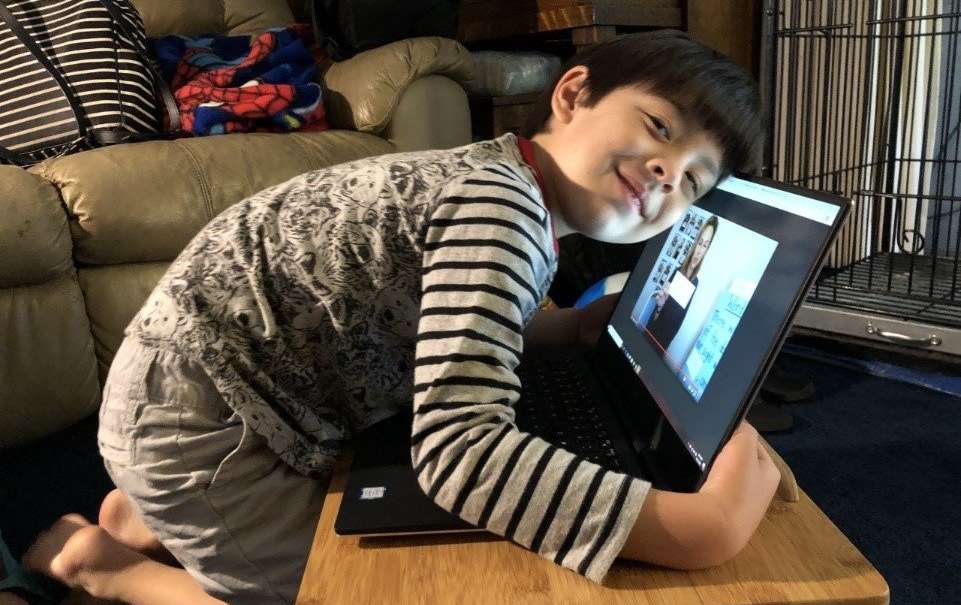

This past June I received an urgent phone request from an extended family member: Would I be willing to tutor him in reading and writing so he could improve as a reader and writer and also have a more interesting life? Ted, as I will call him here, is a 53-year old, single male, who had—due to the pandemic– recently lost his full-time job as a custodian. Home alone in his apartment all day, he sounded desperately sad and lonely. I was more than happy to help him any way I could. So began our twice-weekly, remote learning sessions with the barest technology. Ted had never touched a computer, used email, or texted. We had only our phones, paper and pencil, the U.S. Postal Service, and whatever interesting texts to listen to and read that we both thought—but especially Ted–might be engaging and easily obtainable. I was optimistic. From family gatherings over the years, I knew Ted to be “street smart” (his words), intelligent and endowed with an ironic sense of humor.

I knew nothing about Ted’s educational background other than that he has always had learning disabilities. Each year when I sent him a birthday card with a handwritten message, I kept it simple. I had no idea if he could read it or not. So where and how to begin with him. My many years as a reading specialist and Reading Recovery teacher prompted me to begin with an adapted version of ‘Roaming Around the known.’ I sought to build upon Ted’s strengths and interests and to develop a trusting and warm relationship. Through our conversations, I found out he loved music and that he had a CD player, so that’s where we began—at his comfort level. I also learned he was highly anxious and easily overwhelmed. We kept our sessions to 30 minutes, maximum.

As in working with a new student in Reading Recovery, we initially spent the bulk of our time reading and talking about what we’d read, although at first, that reading involved Ted listening to a book on tape while I was reading the same book in print. Our conversations went beyond basic comprehension to how parts of the text connected to our own lives. I learned how strong his oral language and vocabulary were; I found his insights about a text to be deep and thoughtful.

Reviewing what Marie Clay has taught us, I attempted to create an environment of “confidence, ease, flexibility, and with luck, discovery… The teaching should not start where the teacher is but where the child is!… Share the tasks of reading and writing by doing for the child what he cannot do for himself.” (Clay, 2016, Literacy Lessons Designed for Individuals: Second Ed., Auckland, NZ: The Marie Clay Literacy Trust, p. 29.) Clay believed that by creating a firm foundation for the learner to build upon, the learner becomes willing and eager to begin instruction. This belief holds true for learners of all ages and is especially relevant and necessary for remote learning in a pandemic.

We began each session with a “check in” where I asked Ted how he was doing. As he was speaking, I wrote his words down on my computer—as a record but mainly to document and validate his life—for him. Gradually, as his reading began to improve, I sent these dated pieces to him via mail, and he told me how happy he was to see his words “written on paper,” – that seeing his spoken words written down made him “feel like a writer.” At first, we read those texts together, but he quickly took over reading them on his own. Those personal texts later became the core of our word work, using his language in a context that was meaningful to him to begin to teach onsets, rimes, and important irregular words, what we called “words-to-know-by-heart,” such as “though” and “there”.

Working with Ted reinforced how, first and foremost, we must find ways to establish close and caring relationships with our students. As Ted saw some success, his determination, self-confidence, and stamina grew. In September he asked if we could increase the length of our sessions to one hour. As I am writing this blog mid-October 2020, Ted is determined to complete the reading of his first, full-length, adult book.

Mindsets and Actions That Support Up-and-Coming Readers of All Ages

Once we have signed on, contractually or otherwise, to teach students to read we are obligated to do everything we can to ensure the student(s) becomes an engaged, successful, and joyful reader. Even when technology is severely limited—as it is for Ted and many underserved students and their families—equity issues and the right to an excellent education demand we do all we can to ensure every child and adult becomes a reader.

- It’s never too late to become a reader. (Krashen and McMillan, October 2007. “Late Intervention.” Educational Leadership, Vo. 65 (2).

- Reading texts that are of high interest to the learner is more important than reading levels for engaging and sustaining the reader’s efforts.

- Teaching must be responsive and respectful to the learner—in the moment, in the process, in the plans, in evaluation—and give the learner choice, dignity, and agency.

- Include text offerings beyond books in print and online—such as short magazine articles, phone texts, editorials, news articles, comics, photo-journalism articles, lyrics to songs and raps, poems, audio texts.

- Expand “reading a text” to also mean hearing texts read aloud while following along visually, listening to audiobooks and books on tape, and co-creating texts we then read together.

Regie Routman is a longtime educator, author, and equity champion who promotes and demonstrates engaging, excellent, and joyful literacy practices. Contact her at www.regieroutman.org and follow her on Twitter: @regieroutman.