The Six-Word Memoir: A Tool for Distilling and Sharing Stories

by Lisa Pinkerton, Linda Randall, and Amy Smith

Writing offers the possibility of catharsis and closure; justice and renewal. Writing is a way to seek and to offer support; a way to connect and to celebrate; a way to communicate and to learn. The process of writing can be a revelatory act, a means of expressing our innermost selves. Ultimately, writing is a path for creating and constructing meaning (Clay, 2015, 2016).

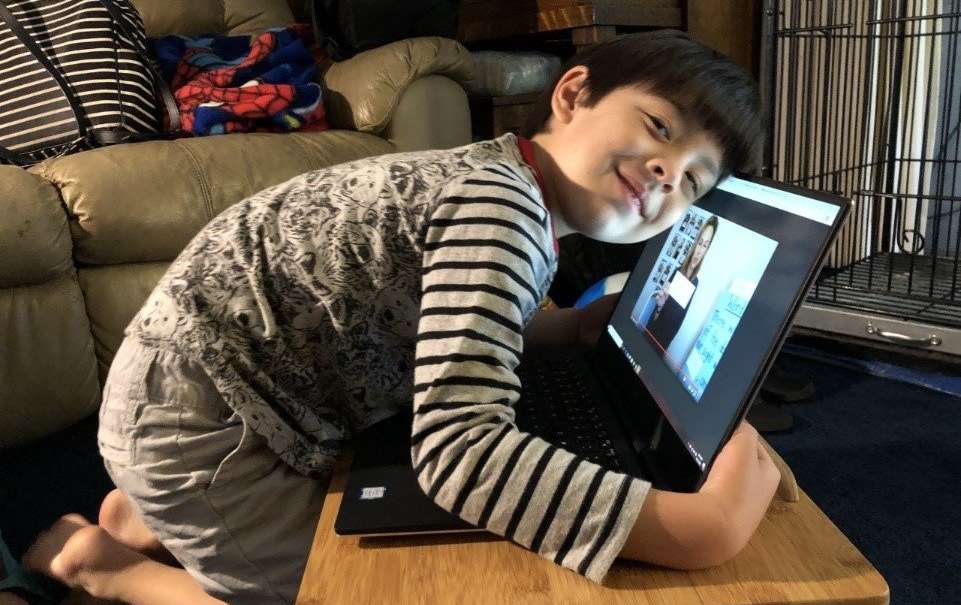

The shift to online instruction, in the wake of COVID-19, sent all of us in search of new ways to create purposeful learning experiences. When we began to work with teacher leaders and teachers following abrupt school closures, our initial response was to help them translate teaching to a virtual context. However, we quickly realized that teachers were carrying such a heavy emotional burden that we needed to create space for them to express and process their anxiety, uncertainty, and personal trauma. Enter the six-word memoir…

Ohio State University Trainer, Lisa Pinkerton, introduced a group of teacher leaders to the Six-Word Memoir project as a reflective tool to use with teachers during online professional learning sessions. Following Lisa’s suggestion, teacher leaders Amy Smith and Linda Randall tried it with their teachers. After writing the memoirs, the teachers engaged in deep reflection about the power of writing to help process and release trauma. Teachers hypothesized that the six-word memoir could help children similarly process their lived experiences and, in so doing, create space for learning. This blog shares our experience of inviting teachers and students to use the six-word memoir as a tool to distill and share stories.

Six Words From Our Teachers’ Perspectives

Although the directions were to write a six-word memoir about any moment from the teachers’ lives, or the collective spirit of many moments, all of them chose to write about COVID-19. The following six-word memoirs reflect teachers’ thoughts about coping, supporting students, and their hopes for the future.

Some days:… introvert, home, family, food, Netflix, happy;

Other days:… crazy, help, need to go somewhere.

—Whitney Webb, Berea Community Schools

Ducks are very cute, but messy!

—Jay Bunch, Madison County Schools

NOTE: Jay was not being figurative; we’re talking about real live ducks he had to bring to his house when school abruptly closed.

Being a mom is very hard.

—Alicia Kelley, Madison County Schools

Checking on loved ones more often.

—Claire Gunner, District of Columbia Public Schools

Acts of kindness in the news.

—Anna Ramsey, District of Columbia Public Schools

Windows down. Wind in my hair.

—Sara Sexton, Berea Community Schools

Family, children, love, food, hope, connection.

—Lisa Frayna, District of Columbia Public Schools

Seeing the smiles of my students.

—Sydney Valdez, District of Columbia Public Schools

Watching children grow despite the distance.

—Bethany Bronson, District of Columbia Public Schools

Loss of control equals weird freedom!

—Melissa Johnson, Madison County Schools

Missing them more than I imagined.

—Terri Cofer, District of Columbia Public Schools

They have embraced change so well.

—Thomas Lynch, District of Columbia Public Schools

Nothing like seeing them in person.

—Lakia Kenan, District of Columbia Public Schools

I hope they are all safe.

—Lauren Conley, District of Columbia Public Schools

Six Words From Our Students’ Perspectives

The following six-word memoirs reflect both the universality and uniqueness of children’s lived experiences:

I love my family. Nice. Grateful.

—Stella, 1st grade

I’m feeling happy; got a puppy!

—Drew, 1st grade

Happy to be healthy at home.

Worried my Dad will get sick.

—Liam, 3rd grade

Gannon: creative funny actor director artist.

—Gannon, 3rd grade

I miss my teachers and friends.

—Emma, 4th Grade

Isolated, Homeschooled, Reading Non-Stop, Living Virtually.

—Carter, 4th Grade

C-Creative; O-Open-Minded; R-Restless; O-Optimistic; N-Nine; A-Adaptable.

—Logan, 4th Grade

Friends will get you through life.

—Dee, 4th Grade

Self-isolation is tiresome and annoying.

—Olivia, 6th grade

Tired, chasing perfect; never stopped running.

—Peyton, 6th grade

A particularly industrious fifth-grader submitted an entire page of six-word memoirs, organized (and color-coded) into three themes: funny, inspirational, and how she’s coping.

We should have bought more crackers.

Doctors are the new Wonder Woman.

DO NOT DISTURB! Reading Harry Potter.

—Aubrey, 5th Grade

Our Six Words About Teachers and Students

Teachers have shouldered a heavy burden, providing invaluable support to children and their families in the midst of chaotic and unprecedented circumstances. To call their actions inspiring is a gross understatement. Children have been equally resilient. To honor their work and effort, the authors of this blog each wrote a six-word memoir about teachers and children, respectively.

Creative, Resilient Teachers: Fearless, Empowered Leaders

Bedhead, Pajamas, Kitchen Tables; Learning happening

—Amy Smith, Reading Recovery Teacher Leader, Madison County Schools

Heroic and exhausted, but lovingly teaching

Fragile and confused, but happily reading

—Linda Randall, Reading Recovery Teacher Leader, District of Columbia Public Schools

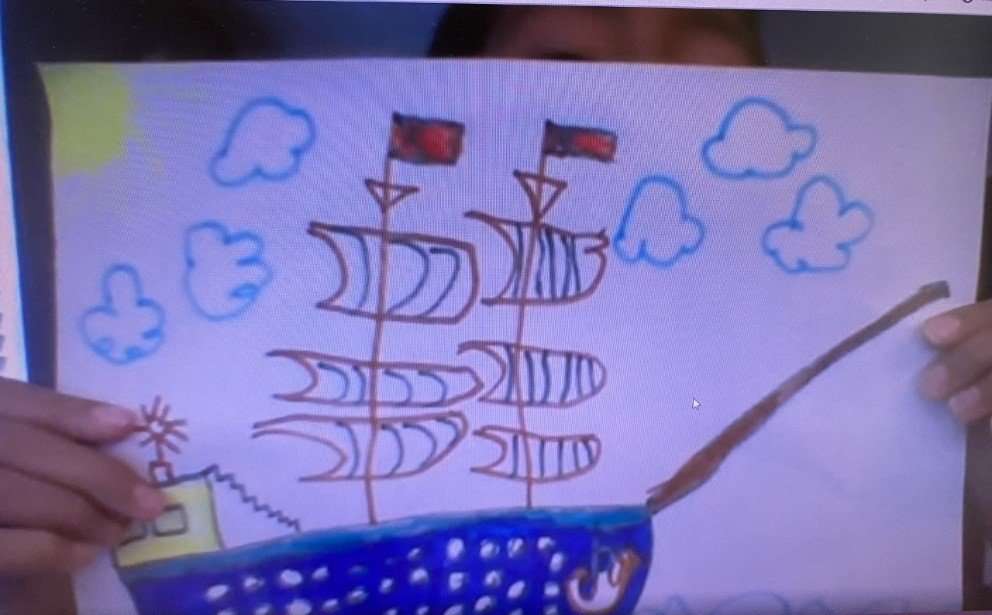

Transforming teaching: Sailing in new directions

Transforming learning: Sailing in new directions

—Lisa Pinkerton, Reading Recovery Trainer, The Ohio State University

Six-Word Memoirs as a Tool for Expression and Catharsis

The six-word memoir writing experience has broadened and reinforced our understanding of the inextricable link between social-emotional well-being and learning. As Lyons (2003) reminds us, teachers “do not give up on the children or themselves. Their spirit and desire to find out how to reach the children emotionally and teach them how to become self-regulated readers and writers is ongoing and time-consuming, but they never quit” (p. 148). Indeed, the process of writing and reflecting upon six-word memoirs elevated our awareness of the emotional burdens we all carry, teachers, and students alike. This experience afforded us the opportunity as human beings to be seen, heard, and acknowledged.

Other teachers have taken up the six-word memoir as a writing tool. When fifth-grade teacher Jane M. Saunders and graduate student Emily E. Smith used this tool to engage their language arts students in writing for self-expression, they described the students’ memoirs as “tiny acts of significance.” And they found that writing the memoirs did wonders for “cultivating confidence and enthusiasm in students” (2014, p. 605).

The teacher and student memoirs shared in this blog are a time capsule of a universally impactful experience. We can’t imagine the number of stories we will have to tell in the end, but have them we will: our children will have them, their families will have them, our communities will have them, our entire world will have them. And although our COVID-19 stories are still being written, we invite you to capture and share a part of that story in a six-word memoir of your own and invite your students to do the same.

Clay, M. M. (2016). Literacy lessons designed for individuals (2nd ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Clay, M. M. (2015). Change over time (2nd ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Lyons, C. A. (2003). Teaching struggling readers: How to use brain-based research to maximize learning. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Saunders, J. M., & Smith, E. E. (2014, May). Every word is on trial: Six-word memoirs in the classroom. The Reading Teacher, 67(8), 600-605.

Lisa Pinkerton is a Reading Recovery Trainer at The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio.

Amy Smith is a Reading Recovery Teacher Leader for Madison County Schools, Richmond, Kentucky.

Linda Randall is a Reading Recovery Teacher Leader for District of Columbia Public Schools, Washington, D.C.