BLOG

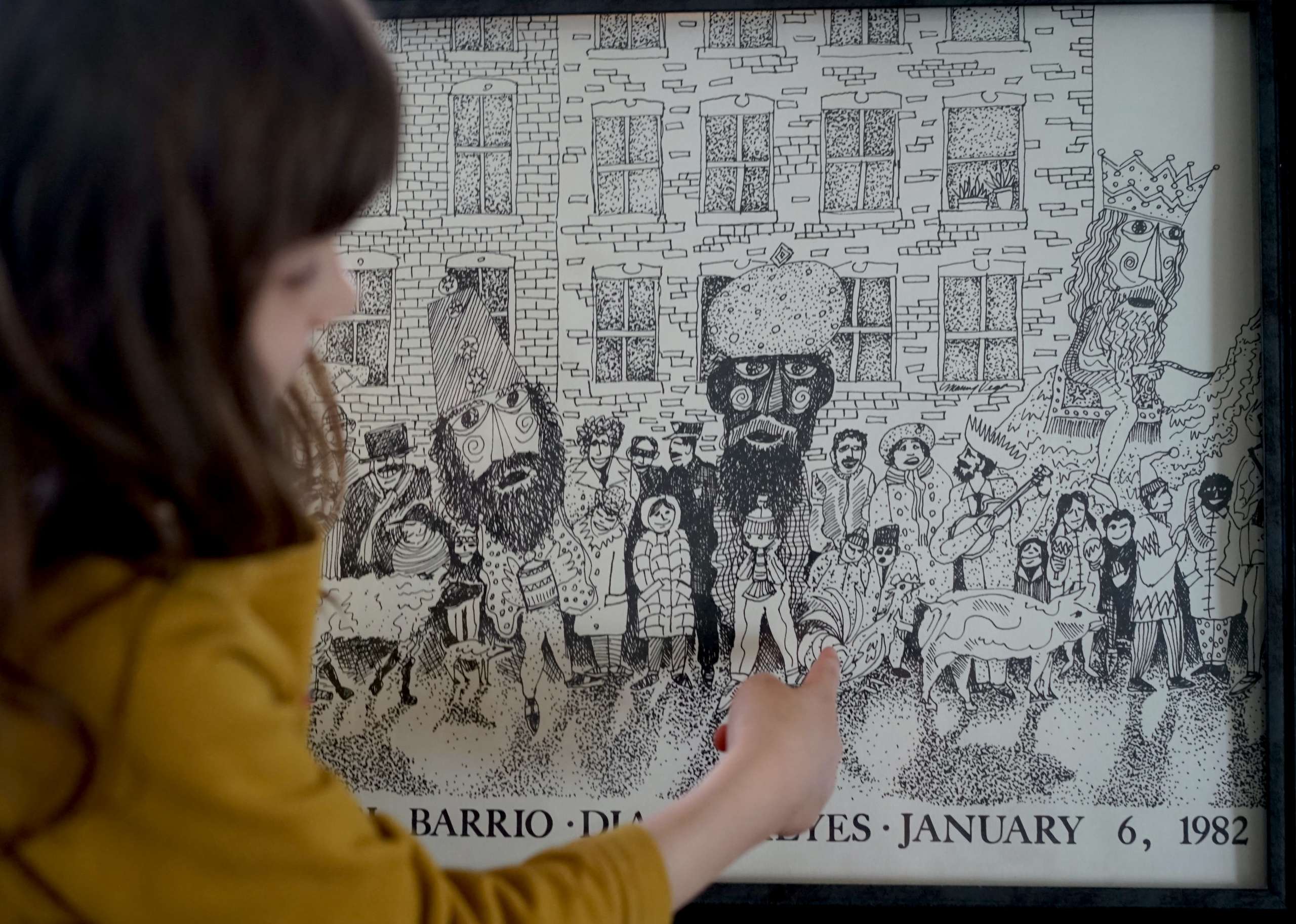

Reading Between the Brushstrokes: Cultivating Critical Thinkers Through Curious Conversations About Art

by Nawal Qarooni Casiano

CONVERSATION AND CURIOSITY

I hopped into the Zoom room from a stool in my bedroom, poised with a pen and ready to take notes. A teacher I work alongside had welcomed me to her first-grade virtual classroom to observe the results of our collaborative planning.

I smiled. All those boxes of eager student faces. A year into the global pandemic, so many kids showing resilience. Though often tired, or physically or emotionally absent, they persevere. Here they all were, over 20 of them. They were there and ready to learn.

The teacher moved to screen-share mode. She began the experience by reviewing their learning from the day before.

“Students! Yesterday we discussed everything we thought when we looked at this painting,” she said, revealing Jordan Casteel’s piece titled God Bless the Child, which we, as teachers, had also analyzed together during PD.

“Remember? Today, I chose this piece of art for us to look at because the artist is from the South side of Chicago, just like us!”

Today would be a day of transference, connecting the skills of analysis from art to reading. Reading a piece of art is just like reading a short text. Art opens doors. Children are naturally curious.

The heads in the virtual boxes nodded knowingly. The teacher shared today’s picture of Elijah on the screen.

Elijah by Charles White is an etching from the early 1900s. In it, a little boy clutches what appears to be a barrier and looks over it with what might be described as sad eyes. I appreciated this teacher’s thoughtfulness for researching and finding a piece of art she knew her students would connect to and learn from while also exposing her students to an African-American artist whose creations underscored racial inequity and imbalanced power dynamics. We had talked about building student language around inequities via art. Ahead of this lesson, we had discussed the importance of leaving space for students to grapple with art as “text,” not rushing in to fill the silences with our own interpretations. We had drawn parallels together between art analysis and alphabetic text analysis and agreed that visual literacy is particularly powerful for students with lower confidence in alphabetic text reading.

“Everyone can look at a piece of art and have a conversation about it,” I had said. “Nobody is excluded from the discussion.”

YOUNG READERS

For the purposes of this initial first-grade art criticality lesson, the students didn’t need to know all that.

“When you look at this drawing, what do you see?” she asked the students.

One by one, they begin to brainstorm, unmuting themselves and naming aloud what they saw.

“I see a head.”

“I think this boy might be spying on somebody,” said another.

“When you’re looking at something normal, your eyes go out. But it looks like the boy is looking over the fence and down.”

Comments from students bounced around, while I transcribed notes for the teacher so she could later review, feel the pride I felt, and determine next steps.

TEACHING ART CRITICALITY: THE PROCESS

Teaching children to ask questions about art is no different than teaching them to ask questions about the world. Criticality muscles are transferable – from art, to alphabetic text, and beyond. In fact, teaching students to visually respond to art by answering seemingly simple questions often spurs rich debate and discussion. The processes in the brain that build connections between what we see and what we infer; what we discuss and what we question replicate the very same reading understandings too.

To begin, we pose three questions to students of all ages:

What do you see?

What do you notice?

What do you wonder?

While there is so much more to ask, keeping it streamlined leaves space for students to cultivate their own curiosity. Teachers might ask students to also look closely at movement, proximity between objects and people, use of light and dark colors, and facial expressions. They might make personal connections. What we hope is that students will make inferences and name what story the art tells, determining why the artist created it in the first place.

This, like all critical thinking, takes practice.

With this springboard for conversation or writing, students typically lead their own initial learning, and the teacher observes, solely jumping in to facilitate. Carving out space to let students grapple with what they notice, including injustice and unfair societal realities.

CLASSROOM PRACTICE

Back in the Zoom room, the first-graders are still looking at Elijah.

“Where do you think the boy is? Whatever you say is fair game. There are no right or wrong answers,” the teacher said.

“Maybe he’s looking over a bathroom stall door?” one student said.

“Is he scared?” another asked. “His fingers are all curled up.”

As the students move into discussing the boy’s feelings, the teacher begins asking questions that are even more inferential. Her questions push the students to provide evidence from the depiction to prove their thinking, make connections to their own experiences, and determine why the artist may have wanted to tell Elijah’s story.

“Why do you think Charles White made this picture? What does he want us to think about?” she asks.

In classrooms with older students, educators might invite art analysis as an option for literary essays, teaching students to name a mood or theme and back up their thinking using evidence from the art. Students might be tasked to create a Flipgrid video describing the story of a piece of art. Regardless of modality, students can share artifacts of their thinking in ways that even the playing field and boost confidence simultaneously.

ANTI-RACIST PRACTICES

When interviewed for a profile in 1978 in the Negro Bulletin, Charles White said, “Art must be an integral part of the struggle. It can’t simply mirror what’s taking place. It must adapt itself to human needs. It must ally itself with the forces of liberation. The fact is, artists have always been propagandists.”

Art literacy provides students with tools to question and dismantle unjust systems. If we recognize that art, like alphabetic text, is not created in isolation or without the beautiful intersectionality (C: Crenshaw) of its creators, then we recognize that teaching students to read art supports the same critical thinking we aim to teach with all text.

At the start of 2021, I collaborated on a project to push Black History study beyond the month of February, to broaden equity and access while celebrating Black abundance and achievement far and wide. It is critical to celebrate Black excellence in all walks of life across every unit of study, without relegating learning solely to stories of Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks. Teachers must expose all students to all stories of Black culture and experience, not solely stories of strife. For the project, I created a Padlet of resources for teachers to share and exalt the art of Black contemporary artists, with folx like Bryan Collier, Bisa Butler, and Ekua Holmes.

Centering Black artists in art criticality lessons with students is one way to provide inclusivity. Because most art is a form of resistance, like Charles White said, we can teach students to learn another way to combat injustice. The Padlet includes information about each artist, from biographies to videos that explain their processes and reflections on their place in the world, not dissimilar to author interviews and video book trailers. The Padlet provides communication sets for knowledge-building to ensure students know they can learn in a variety of ways- thus teaching in more equitable ways.

What’s more, is the access that art allows. All students can read art and hold conversations around what they see, thereby strengthening their criticality muscles and allowing for clearer transfer when they approach alphabetic text.

But it doesn’t end there. Art and images also evoke feelings, just like books. All art tells a story.

“How does this art make you feel inside?” the teacher prompted.

“I feel impatient,” one child responded.

“I feel worried,” another said.

“I feel scared. Because he wants to hide,” said another.

“I am so proud of you,” the teacher concludes. “You can ask yourself these very same questions when you read a book, too.”

Citation: Charles White biography from the MOMA

Nawal Qarooni Casiano is a literacy consultant, educator and writer based out of Chicago, IL. She and her team at NQC Literacy support a holistic, balanced model of literacy instruction in dozens of schools and districts. She is a contributing author to the Two Writing Teachers and Choice Literacy education blogs, and mother to four multilingual, multiethnic kids who shape the way she understands literacy and education. You can find her on Twitter @NQCLiteracy or in Chicago’s Logan Square.

Nawal Qarooni Casiano is a literacy consultant, educator and writer based out of Chicago, IL. She and her team at NQC Literacy support a holistic, balanced model of literacy instruction in dozens of schools and districts. She is a contributing author to the Two Writing Teachers and Choice Literacy education blogs, and mother to four multilingual, multiethnic kids who shape the way she understands literacy and education. You can find her on Twitter @NQCLiteracy or in Chicago’s Logan Square.

THE JOURNAL OF READING RECOVERY

Spring 2024

Constructing a More Complex Neural Network for Working on Written Language That Learns to Extend Itself by Carol A. Lyons

Reading Recovery IS the Science(s) of Reading and the Art of Teaching by Debra Semm Rich

Predictions of Progress: Charting, Adjusting, and Shaping Individual Lessons by Janice Van Dyke and Melissa Wilde

Teachers Designing for Context: Using Integrity Principles to Design Early Literacy Support in Aotearoa New Zealand by Rebecca Jesson, Judy Aitken, and Yu Liu