Using Share Time to Inspire and Instruct Writers

by Leah Mermelstein

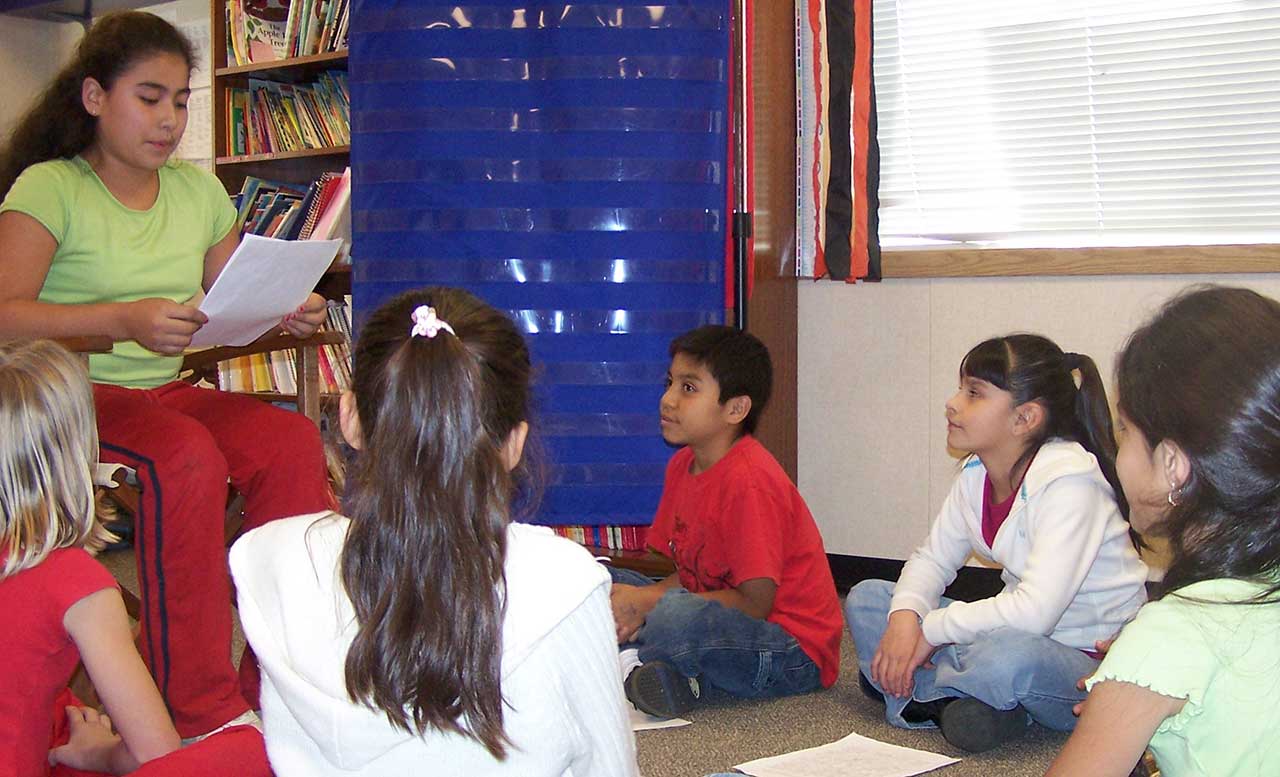

Recently, I was speaking with a group of fourth-grade teachers who use The Teachers College Writing Units of Study. They had just taught a minilesson about using ‘boxes and bullets’ as a planning tool. Not surprisingly, some students had success with the lesson, while others struggled. It seemed natural for us to brainstorm possible follow up minilessons, but after a few minutes, we wondered aloud if we could better address this issue with a few well thought out share sessions. We came up with a few open-ended questions and over the next few days, the teachers used those questions to jump-start conversations with their students. The teachers were amazed by the kids’ conversations during the share sessions. They saw firsthand how conversations deepened the students’ understanding of ‘boxes and bullets’ and untangled some of their confusions about planning in general. Not only that but by listening in to these conversations, the teachers got some great ideas for future lessons. Share sessions, when done thoughtfully are as instructional (if not more so) than minilessons or conferences. The question then is: How can we ensure that the shares that we do in our classroom are instructional and engaging for everyone?

Shares as Conversations:

In my book, Don’t Forget to Share, I talk about how share sessions in the writing workshop are most useful when teachers structure them, not as a second minilesson, but as a time for kids to have instructional conversations with one another. When I’m conducting share sessions as conversations, I begin by telling the kids the topic of the conversation. Then, kids talk to one another in partnerships and finally, they talk together as a group. In my book, I outlined four different types of share conversations (Content, Craft, Process, and Progress). Over time, I have layered new thinking onto each of these shares, and have had fun developing some new share session ideas as well.

Ultimately, the kinds of shares you can do with your kids are endless. Here are my current five favorite share session conversations. If you’ve read my book, you’ll recognize many of them, but you’ll see some new ones to try out as well.

Content: This type of share starts with a student sharing either her entire piece or a part of her piece. The class retells the piece to make sure they understand it. Finally, they ask questions about the parts that confused them and/or the parts they want to know more about. Based on these questions, the student will decide what revisions she’ll make (if any). Just recently, I did a content share in a kindergarten class. The little girl wrote a story about having a play date with her friend. She and her friend were playing under the table. On the last page, she wrote that she was sad. After the class retold her piece they asked questions: Why were you under the table? Why were you sad? She explained that they were playing family under the table and that she was sad because her mother came early and she didn’t want to go home. Ultimately, she revised her story by explaining why she was sad.

Craft: This type of share starts with one child sharing the craft technique he/she tried. The craft might be directly connected to what was taught in the minilesson or it might be something that popped up during a conference. The other kids come to the share with their current writing piece, a pencil, and/or a post-it note. After the child shares, the other kids reread their writing checking to see if the craft technique would work for them. If it does, they make some sort of notation to remind themselves of what they want to try. Finally, they share their findings with one another.

Minilesson: This share starts with a question that is related to the minilesson. The kids talk about the question as a way to clarify their ideas and deepen their understanding of what was taught. Recently, I conducted a minilesson helping students organize their table of contents in their non-fiction books. After the lesson, many kids were still confused and unable to make substantial changes. During the share, I asked the following questions: What kinds of changes could a writer make to their table of contents? How would those changes help? Because they were talking as a way of thinking, they struggled at times to find the right words but the talk itself brought to a new level of understanding.

Process: During a process share, the teacher poses a question that gets kids to reflect upon some part of the writing process (How does rereading help you? What kinds of planning can you do in your Writer’s Notebook? How does that planning help you with drafting? How have you grown in this unit? What can you do now that you couldn’t do in the beginning of the year? How can you take what you learned in this study to the next study?) The kids talk about the question as a way to deepen their understanding of that part of the process, as well as to help themselves transfer their learning into ongoing work.

Spelling: In a spelling conversation, the teacher finds a student who has spelled a word incorrectly and uses that word to provide spelling instruction for all students. The teacher first shares what the student did well and then shows the class the spelling rule or pattern that this word follows. Finally, the kids talk to one another, trying to generate other words that follow the same rule or pattern. Recently, a student I worked with had spelled ‘played’ as ‘plad.’ First, I pointed out to the class how the child listened closely to the beginning sound of played. Then, I showed the kids how in this word, the long ‘a’ was represented by ‘ay’. Then, the kids talked to one another, brainstorming other words where the long ‘a’ was represented by ‘ay’.

Leah, a student I had the pleasure of working with, called share conversations the ‘bits and pieces’ of all of us. I love that description and hope that if you conduct your share conversations, you will be able to use the bits and pieces of all of your students to help everyone become more engaged and skillful writers.

Leah Mermelstein is a literacy consultant who works with teachers, literacy coaches, and principals. She is also the author of four books on the teaching of writing and is thrilled to be a presenter at the 2019 National Reading Recovery & K-6 Literacy Conference. Hear more about how talk can instruct and inspire writers at her session titled, Conversations That Inspire and Instruct Student Writers. You can find here at @MermelsteinLeah or www.leahmermelstein.com.