BLOG

The Balancing Act: Integrating sources of information in text reading

by Maryann McBride

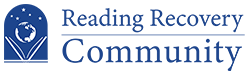

On a recent teacher visit, the teacher introduced “Billy Can Count.” It was a very well-chosen book, but as often happens in Reading Recovery, the teacher got a surprise on the first page of the text. Unfortunately, the surprise continued throughout the entire book. Here’s how the first page went:

So, the child stops at bowls. The concept had not been discussed in the book introduction as the child easily talked about helping his mom set the table and named a variety of utensils and items to be placed on the table. And one of the teacher’s goals was for the child to use visual information, especially the first part of words with meaning and structure to monitor and search in his reading.

The teacher prompted the child to check the picture (which the child did consistently throughout the lesson) and think what mom might want Jack to put on the table. Without turning back to the print, the child said “bowls” and the teacher praised the child. The teacher was happy with the correct response, but should we be?

My view is probably not. It is critical as Reading Recovery professionals that we know not only that the child got it correct but how this was done. This attempt was solely based on the picture with little, if any, evidence that visual information was attended to.

Thinking About Multiple Sources of Information

Clay reminds us often in the 2016 Literacy Lessons Designed for Individuals Second Edition that “Early intervention teachers observe children’s reading behaviours very closely” (p. 110). Without close observation, we might miss what the child did and didn’t do.

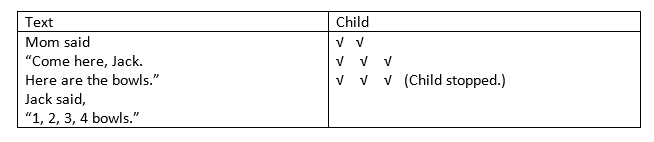

Also, Clay’s theory of literacy processing which guides the Reading Recovery procedures is based on the integration of multiple sources of information in text. Our role in the Reading Recovery lesson is to guide the child “to pay particular attention to four kinds of information the young readers must become aware of and learn to work with. Different kinds of information may be checked, one against another, to confirm a response or as a first step towards further searching” (p. 129).

While Clay says the above diagram is a simplistic representation of what readers need to do, the diagram is meant to help the teacher think about what sources of information the reader might have used.

Clay reminds us that “if the child has a bias towards the use of language information, the teacher’s prompts will need to direct him to print detail and to using what he knows. She may get him to confirm an attempt by attending to initial, final and later, medial letters, first in the spoken and then in the written word” (p. 140).

This advice is critical to children beginning to integrate the sources of information, and the sooner this happens, the quicker acceleration will be. What would that look like had the teacher in this example taken a different course of action?

Using Questions and Prompts

Clay provides many options for handling this situation. Here are a few that might help you if you find yourself in this situation.

You might begin the action by asking the child, “Why did you stop? What did you notice?” Keep in mind that teaching here might not be a good idea if the letter b is unknown or easily confused. But in the above case, that confusion doesn’t exist. It’s best to teach on items that are not confusions or contain confusions.

Sometimes the child will response with, “I don’t know that.” So, you might go to the most support on the scale of help and make the grand gesture. “The teacher might construct part of the word making it larger in some grand manner. (Use gestures, a whiteboard or magnetic letters)” (p. 152). I would put the b down and say, “Think about your story and what might begin with this letter that you know.”

If bowls falls out of his mouth, then make him check it or ask him, “What sounds can you see in that word?” That question is used if the child already knows some of the letter-sound relationship in the word, for example, /b/ /l/ and /s/. In this way, you are balancing the use of the sources of information. Then tie it up with, “Would that make sense and sound right, and look like that?”

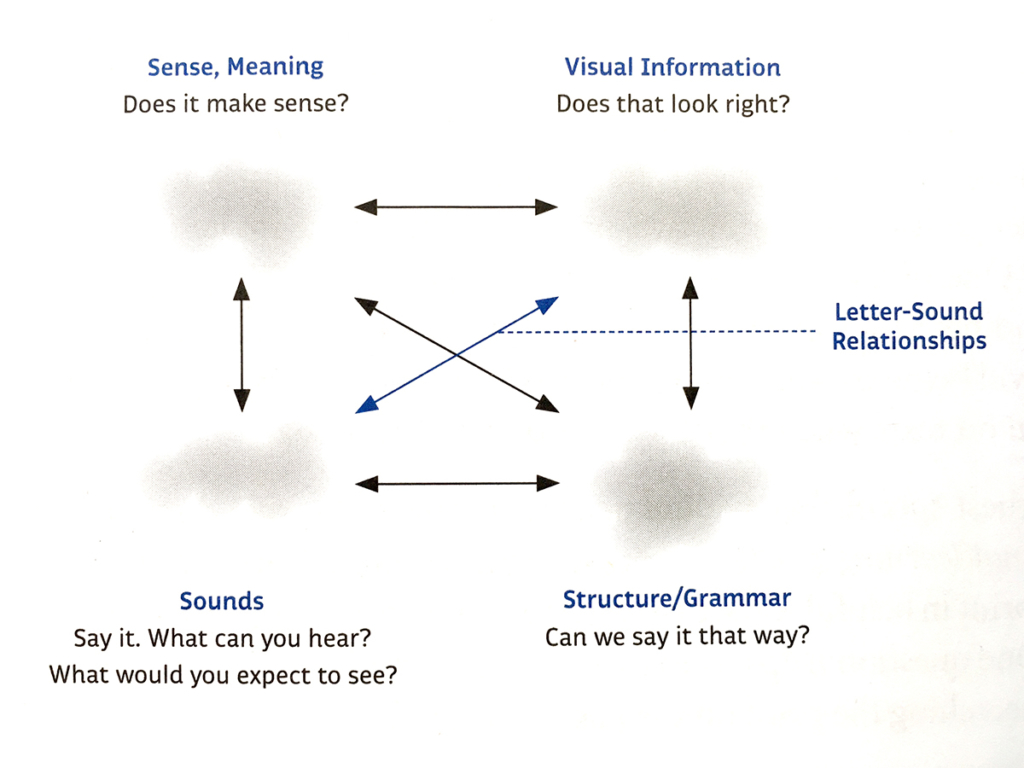

The goal is if the child used meaning and/or structure, then the teacher should call for the use of visual information to predict or to check a prediction.

Suppose you find yourself in the situation of the teacher in the example, where she prompted for checking the picture and without any attention to print the child says “bowls.” Then instead of praise, yet, you might say, “Are you right? How do you know?”

If the child continues to refer to the picture then ask, “Does it look right?” followed by, “What letter would you expect to see at the beginning of bowls?” Then have the child check it and say, “Now it looks right and make sense.”

Another possibility is to move further up the scale of help: “The teacher articulates the part clearly (a hearing prompt) and the child locates the part” (p. 152). Make sure you have the child locate the part you have sounded, even if the word just rolls out of his mouth. This task has to be turned over to him. And again, tie it up emphasizing that you have to make it make sense and look right.

Additional prompts and suggestions can be found on pages 136-152. Our work in Reading Recovery is to get our students to use all sources of information. This will ensure continued progress as readers and writers. As Clay reminds us at the conclusion of the text on page 195 …

“And in the end

it is the individual adaptation

made by the expert teacher

to that child’s idiosyncratic competencies

and history of past experience

that starts him on the upward climb

to effective literacy performances.”

Maryann McBride is a Reading Recovery teacher leader at Clemson University and a 2018 National Reading Recovery and K-6 Literacy Conference presenter. Follow her on Twitter @Maryann081153.

Maryann McBride will be a speaker at the 2019 National Reading Recovery & K-6 Literacy Conference, February 9-12, in Columbus, OH. Her session is titled, “Fluent, Flexible, and Fast with Higher Level Text”.

Any views or claims expressed in The Reading Recovery Connections Blog are those of individual authors, not RRCNA.

THE JOURNAL OF READING RECOVERY

Spring 2024

Constructing a More Complex Neural Network for Working on Written Language That Learns to Extend Itself by Carol A. Lyons

Reading Recovery IS the Science(s) of Reading and the Art of Teaching by Debra Semm Rich

Predictions of Progress: Charting, Adjusting, and Shaping Individual Lessons by Janice Van Dyke and Melissa Wilde

Teachers Designing for Context: Using Integrity Principles to Design Early Literacy Support in Aotearoa New Zealand by Rebecca Jesson, Judy Aitken, and Yu Liu