Spotlight Speaker: Allison Briceño

Don’t miss this presentation on Sunday, January 28 and Monday, January 29! Join Dr. Allison Briceño for Creating Conscious Classrooms: Using Diverse Books for Anti-Racist Teaching.

Dr. Allison Briceño is an Associate Professor in the Department of Teacher Education at San José State University, where she coordinates the Multilingual and Multicultural Literacy Education MA program. Prior to SJSU, Dr. Briceño was a dual language teacher, reading specialist, literacy coach, and district literacy coordinator. Her research explores the rich literacy practices of multilingual students and linguistically and culturally sustaining pedagogies.

In this session, attendees will center the lived experiences of diverse students to support language, literacy, and identity development. Justice-oriented literacy practices will be used to practice integrating language and literacy with social justice. Diverse text selection and use in today’s contested climate will be addressed.

Don’t miss out by registering for LitCon: National K-8 Literacy & Reading Recovery Conference!

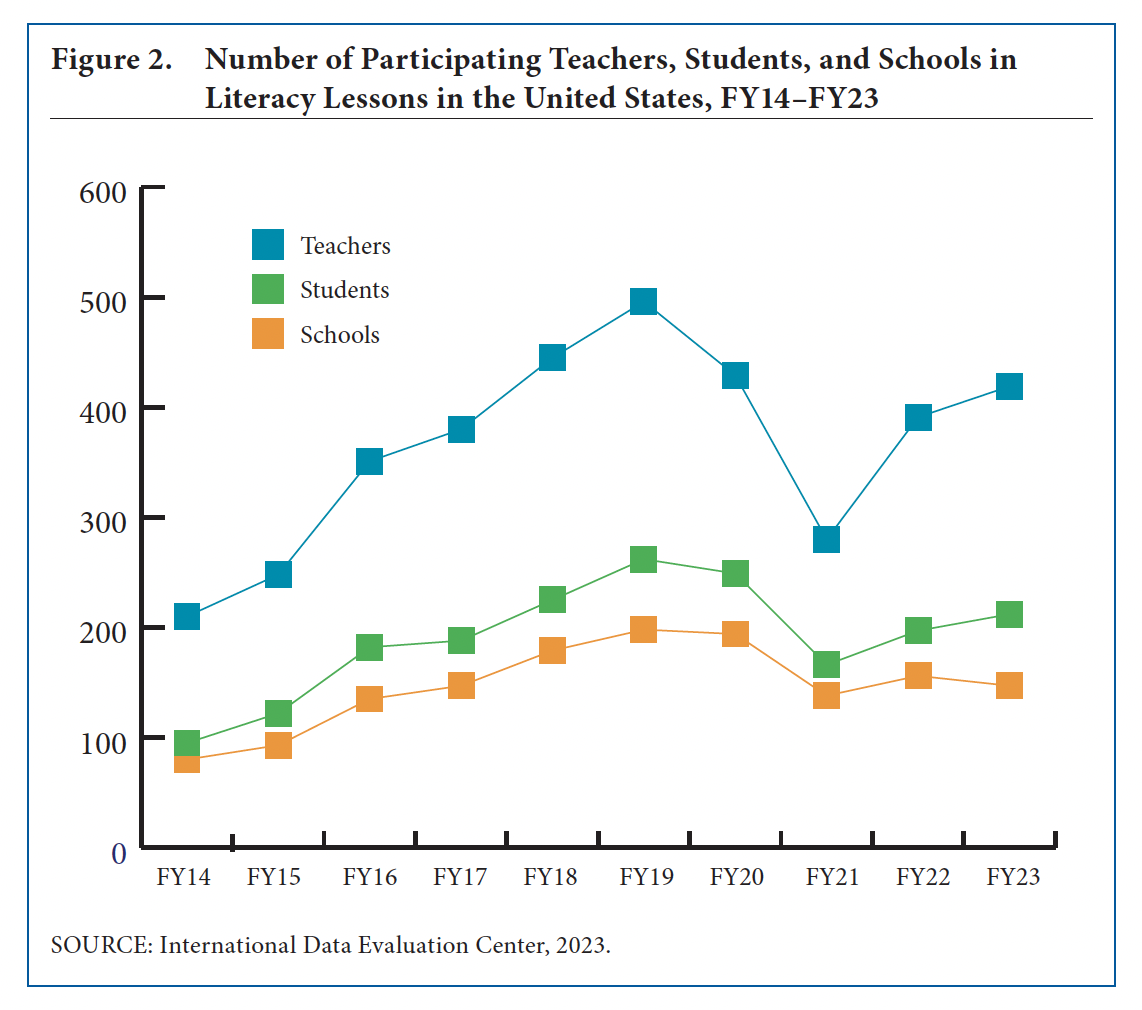

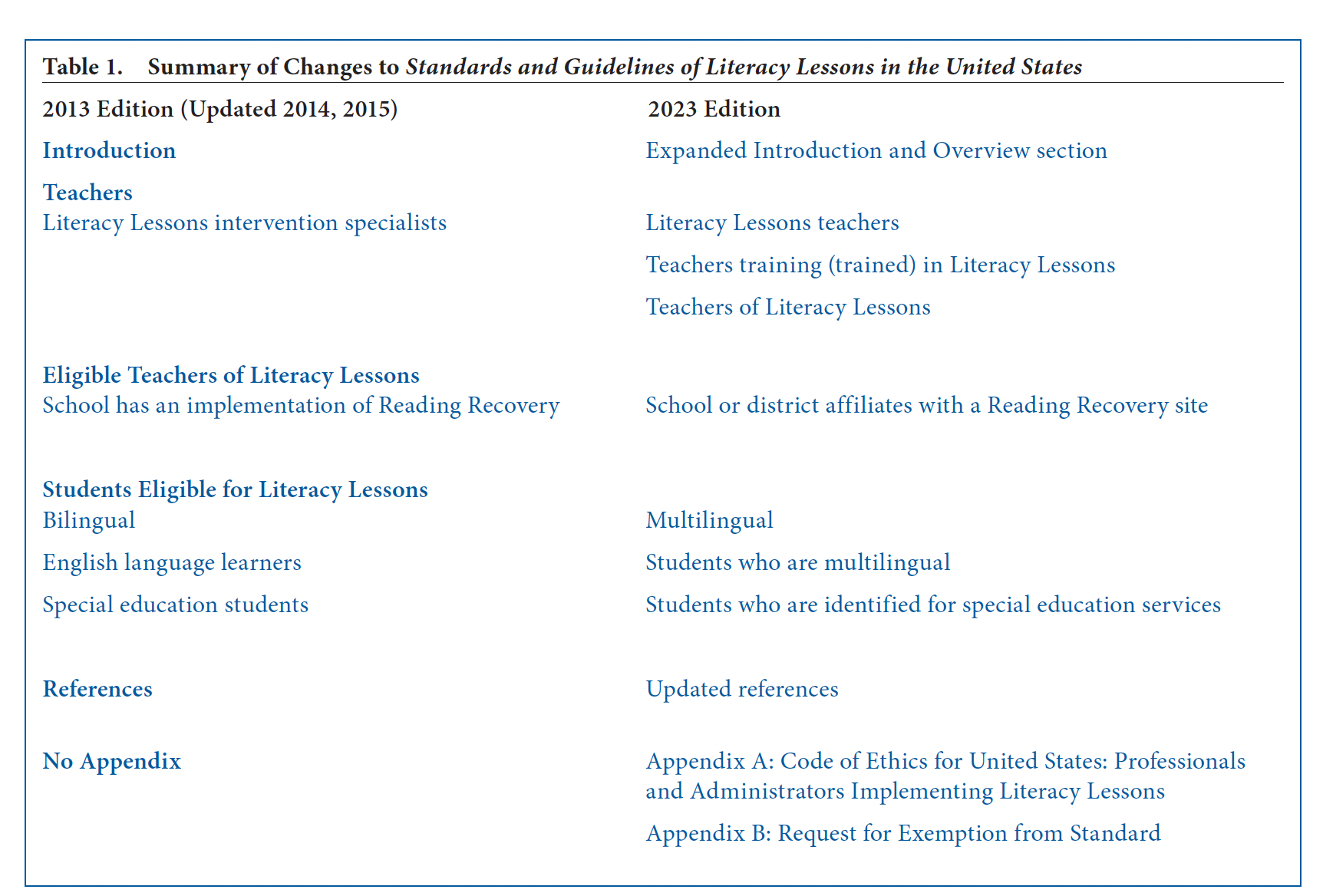

The training in Reading Recovery teaching procedures needed by teachers of special education students and English language learners has been developed and implemented with the trademarked title Literacy Lessons.…within the existing infrastructure for training and dissemination established by the holder of a national trademark

The training in Reading Recovery teaching procedures needed by teachers of special education students and English language learners has been developed and implemented with the trademarked title Literacy Lessons.…within the existing infrastructure for training and dissemination established by the holder of a national trademark