BLOG

Intervention Essentials: Lessons With Emergent Bilingual Students

Mary D. Fried, The Ohio State University

What are some essential shifts in teaching when the Reading Recovery® child is also learning English?

Reading Recovery is an inclusive intervention that is successful with a wide range of children of varying diversities. Among these learners are emergent bilingual students whose accelerated progress has been documented repeatedly (Ashdown & Simic, 2000).

Most recently, both the i3 investigation (May et al., 2016) and a reexamination of annual data reported to the International Data Evaluation Center (Elzy et al., 2019) confirm the efficacy of Reading Recovery instruction with emergent bilingual students. The results of these studies show not only the accelerated progress achieved by these students but also present evidence of narrowing of the achievement gap among emergent bilingual students (Elzy et al., 2019). This success results from effective instruction provided by Reading Recovery teachers meeting the individual needs of children learning a new language and literacy simultaneously.

In my work with teachers and teacher leaders, I have been asked for advice regarding the instruction of emergent bilingual students. In general, emergent bilingual students are successful in Reading Recovery lessons when their teachers attend to the individual language competencies they present; nurture their competencies in speaking, reading, and writing in English as well as their home language; and have awareness of their first language and cultural heritage (RodríguezEagle, 2009). In this article, I share questions and recommendations gleaned from my opportunities to teach children and observe lessons for over 35 years. Most of the children I have taught were of widely diverse language backgrounds and were also receiving language support services.

What do you recommend I do to get started? Two of my students are receiving language support services. One is chatty; the other is very quiet and shy.Start the way you always do in Reading Recovery because the framework of the lessons—beginning with Roaming Around the Known—is designed for the teacher and child to work together reading wonderful stories while also talking, writing, and getting to know each other. You will not only have excellent opportunities to observe the child’s strengths, but the Roaming lessons will also give you the opportunity to gain the child’s trust, to make it easy for the child to respond, and to encourage the child to talk with you. Observation, a safe environment, and supportive interactions are important goals of these sessions.

Administer the Record of Oral Language (ROL; Clay et al., 2015) as soon as possible. This will give you insights regarding the child’s control of English oral language structures and make you aware of the support you must provide when introducing new books. The ROL sentence repetition tasks will also help you determine the support needed by the child to compose and write a message.

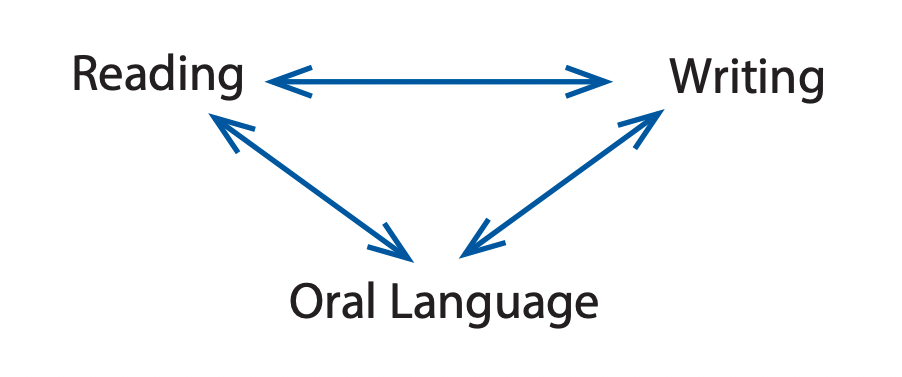

Assure that the lesson framework and your support create reciprocity (Clay, 2016, pp. 23, 77, 106). I think of reciprocity as the golden triangle of literacy learning (Borba, 2004).

For emergent bilingual students, what they learn in reading will help them in writing and vice versa. Their home language is also an important component in their full linguistic repertoirs. Both will help children expand their English language acquisition.

Clay (2016) recommends recording the child’s “longest utterance” (pp. 31, 79) during Roaming. Multilingual trainers in Reading Recovery recommend recording the child’s longest utterance daily.

Are there any adjustments I should make in my teaching when we begin lessons?

The first multilanguage learner I taught was Rachel, from Zimbabwe. Her first language was Shona and she had completed 1 year of school in Zimbabwe where English is the primary language used by schools and the government. I recommend that you do a search of the first language of the child to learn the characteristics of the language and the culture of the country.

After a pleasant series of Roaming sessions with Rachael, the first books I introduced were Level 3 books, and we hit frustration. I shifted to Level 2 with success for Rachel, but Level 3 continued to be too difficult. I then looked closely at her performance on the ROL. Finding that Rachel repeated very few of 14 sentences correctly at Level 1, I learned I needed to adjust my introductions of new books. As Marie Clay once said to me, “The purpose of ROL is not to label or put a score on the child but to inform the teacher.” As soon as I shifted to provide more support and rehearsal of language structures during book introductions, Rachel was successful with Level 3 books.

Soon Level 4 books were in her instructional range and progress was made in every lesson. Rachel not only needed to hear and practice the language structures of the new book, but she also benefited from reading them in her familiar books. This helped her to read more-complex text successfully and to expand her oral language in English. The added aspect of seeing the phrase or sentence was very important for many of my students.

What about writing? Do you think my student will be able to compose and write a message or simple story? Remember, one child hardly ever speaks.

Yes, with your support! I have cautioned many Reading Recovery teachers to be judicious. For example, after a brief conversation about a book or topic, do not just ask the child to restate the message by prompting “What could you write about that?” (Clay, 2016, p. 81). The ROL will help you identify children who will find replying to that question extremely difficult, especially in early lessons, and those who will have little trouble responding to that prompt.

For children whose English you are supporting, record the child’s story as presented to you. Then repeat it back to the child in appropriate chunks (usually phrases or one short sentence at a time). After writing the first sentence, teachers may ask a guiding question to elicit more talking and writing within the same writing episode (Clay, 2016, p.81). This is very effective.

Najib, my student from Niger whose first language was Arabic, took great pride in writing about a book he had just read. He taught me the value of writing about the story, then rereading his written story during the next lesson, and adding another part to create a sustained story with a beginning, middle, and end. He excitedly asked if he could read it to his ESL teacher. For his next lesson, I had made a copy of his story so we added pictures and speech bubbles. He smiled a big smile as we stapled his story together creating his own book to read in his ESL class and at home.

In early lessons, writing about the book was a safe and secure way for my English learners to generate stories. Adding some pictures, labels, and/or speech bubbles brought the stories to life while also increasing concepts, vocabulary, and oral language opportunities. I still remember the look of pride on Najib’s face when he closed his Level 14 book and said, “Now I know two languages: Arabic and English. I think I will learn 10 more!” What I knew for sure was that he had a better chance of doing that than I did! It has been a joy to teach emergent bilingual students.

Mary D. Fried is a Reading Recovery trainer emeritus with the North American Trainers Group. Formerly she was a clinical trainer for Reading Recovery at The Ohio State University.

References

Ashdown, J., & Simic, O. (2000). Is early literacy intervention effective for English language learners? Evidence from Reading Recovery. Literacy Teaching and Learning, 5(1), 27–42.

Borba, M. (2004). Building the literacy triangle for English language learners: Reading Recovery, the classroom, and the home. The Journal of Reading Recovery, 3(2), 31–37.

Clay, M. M. (2016). Literacy lessons designed for individuals (2nd ed.). Heinemann.

Clay, M. M., Gill, M., Glynn, T., McNaughton, T., & Salmon, K. (2015). Record of oral language: Observing changes in the acquisition of language structures (updated ed.). Heinemann.

Elzy, J., Williams, J., & Brymer-Bashore, J. (2019). The impact of intentional and purposeful practice with English language learners in Reading Recovery. The Journal of Reading Recovery, 19(1), 45–53.

May, H., Sirinides, P., Gray, A., & Goldsworthy, H. (2016). Reading Recovery: An evaluation of the four-year i3 scale-up. Consortium for Policy Research in Education.

Rodríguez-Eagle, C. (Ed.)(2009). Achieving literacy success with English language learners: Insights, assessment, instruction. Reading Recovery Council of North America.

THE JOURNAL OF READING RECOVERY

Spring 2024

Constructing a More Complex Neural Network for Working on Written Language That Learns to Extend Itself by Carol A. Lyons

Reading Recovery IS the Science(s) of Reading and the Art of Teaching by Debra Semm Rich

Predictions of Progress: Charting, Adjusting, and Shaping Individual Lessons by Janice Van Dyke and Melissa Wilde

Teachers Designing for Context: Using Integrity Principles to Design Early Literacy Support in Aotearoa New Zealand by Rebecca Jesson, Judy Aitken, and Yu Liu