Follow My Journey: Just Keep Swimming

Join us this year in a five-part series while we follow the journey of Heather Cherry as she trains to be a Teacher Leader.

By Heather Cherry

Long before Marie Clay began building her legacy in the world of literacy, another world changer by the name of Marie Curie said, “Life is not easy for any of us, but what of that? We must have perseverance and above all, confidence in ourselves. We must believe that we are gifted for something and that this thing must be attained.” These words so clearly describe my feelings about starting this journey to training as a Reading Recovery Teacher Leader.

It won’t be easy, but what in life that’s worth having is? I will surely experience a lot of challenges along the way. I already have, but I am determined to persevere. I have to believe in myself and trust that I have this opportunity because I have something, a gift of some kind, that will serve my Reading Recovery community beyond the students in my classroom.

One of my favorite quotes about leadership is, “Be the kind of leader others want to follow,” by John Maxwell. I am blessed to have had the best teacher leader, Jan Grisham, for four years. She is undoubtedly someone we all want to follow, and I’m trying to be her shadow this year as I strive to glean all her knowledge and wisdom before she retires (after 12 years as TL!). From my first Reading Recovery training experience until now, Jan has shown me tremendous grace and patience. She continues to invest so much of herself to ensure my success as a Teacher Leader.

Heather and Jan

My first four weeks of training have been a bit like the movie Finding Nemo, where the little fish, insecure and scared, sets out on a journey that has him facing frightening things like sharks, rip currents, and fishing nets. I, too, felt a little insecure when delivering my first professional development to trained teachers. Thankfully, they were very kind to me and not like sharks at all. Like the little fish, though, I was caught up in a rip current of sorts. However, mine was trying to observe my teacher leader as she taught the assessment training class, while I attended my assessment training class, while trying to assess my students and keep up with the other dozen or so things on my must-do list. Then, there was the issue of the net. It wasn’t a fishing net, but rather an overwhelming feeling of, “I’m not going to make it out alive, or at least through this week, with all I need to finish.”

Thankfully, like Nemo, I just kept swimming and made it through my first month! I’m feeling hopeful and excited for what is next. Now, for the open water (in other words, lesson analysis and oral exams)! Bring on the sharks! Just kidding, I really am scared of those.

The Reading Recovery Council of North America is thrilled to announce Heather Cherry as the 2023 Teacher Leader Award recipient. Heather represents Broken Arrow Public Schools in Oklahoma. A graduate of Northeastern State University with over 22 years of experience teaching, she will be part of the first training class at Oklahoma State University.

The Reading Recovery Council of North America is thrilled to announce Heather Cherry as the 2023 Teacher Leader Award recipient. Heather represents Broken Arrow Public Schools in Oklahoma. A graduate of Northeastern State University with over 22 years of experience teaching, she will be part of the first training class at Oklahoma State University.

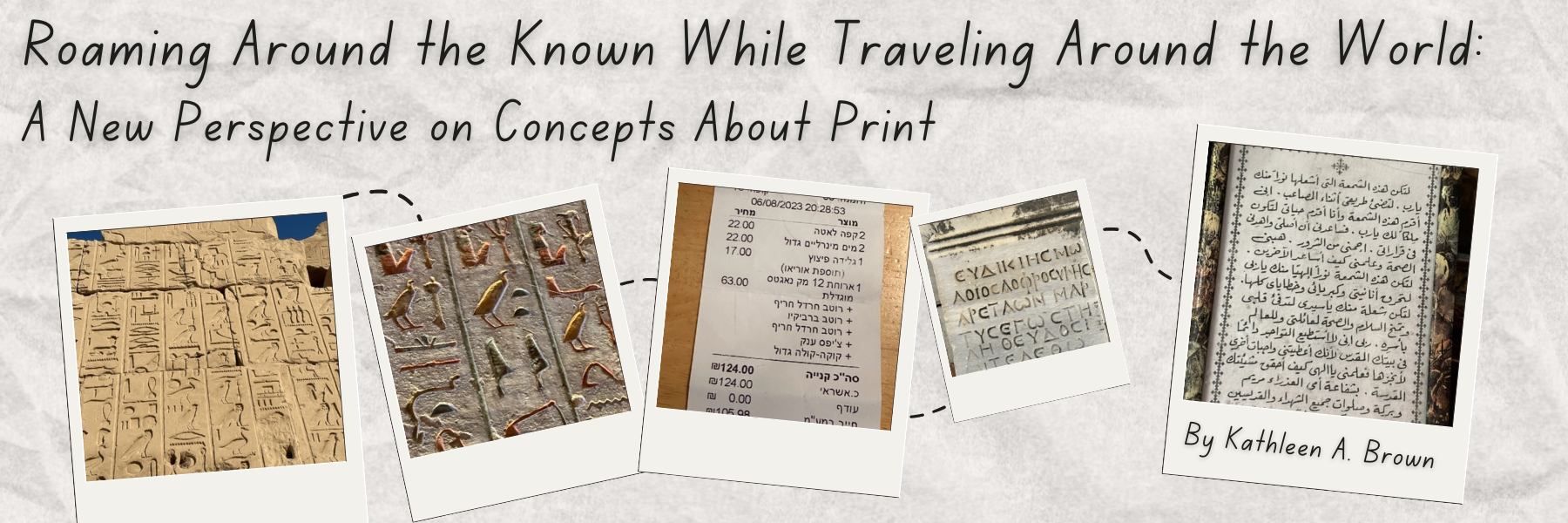

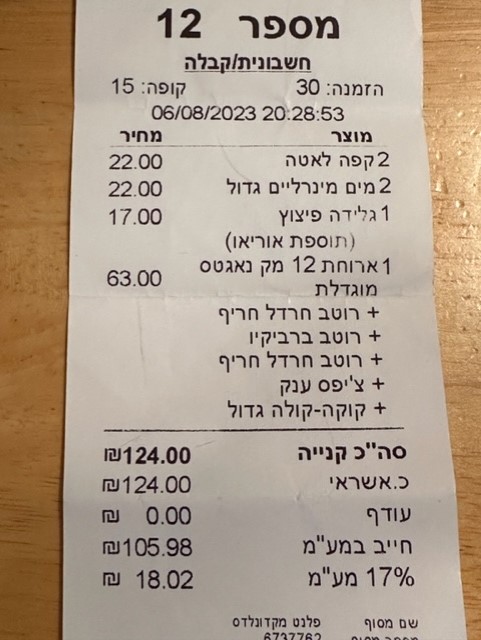

Kathleen A. Brown has worked for 37 years as a classroom teacher, literacy specialist, staff developer, and Reading Recovery teacher. She has served as the Reading Recovery teacher leader in a large urban district in California for the last 22 years. Kathleen has provided early literacy training and coaching for the district and has presented at local, state, and national conferences.

Kathleen A. Brown has worked for 37 years as a classroom teacher, literacy specialist, staff developer, and Reading Recovery teacher. She has served as the Reading Recovery teacher leader in a large urban district in California for the last 22 years. Kathleen has provided early literacy training and coaching for the district and has presented at local, state, and national conferences.

Catherine Monda is from Sarasota, Florida. She has been a teacher for over 32 years and a Reading Recovery teacher for seven.

Catherine Monda is from Sarasota, Florida. She has been a teacher for over 32 years and a Reading Recovery teacher for seven.