BLOG

Navigating in Reading Recovery

by Sandy Brumbaum

This past spring break, I met my daughter in Florence. Because she had been working in Greece for the past year, she had an EU data plan, so we used her phone to navigate our way around this walking city. I became the follower, passively letting her lead me from one place to another. I rarely knew where I was with the long narrow streets and the tall brown buildings looking much like the next one. I usually didn’t know we were back on our street until I saw the familiar scaffolding a block from our Airbnb apartment. I noticed this late in the week when I looked at a map and realized there were several significant plazas in Florence, and I didn’t have a clue which was which, even though I knew we’d been to each one. They all looked the same to me.

Our apartment on Via dei Pilastri Walking towards the Duomo

Navigation is also an issue in teaching, and Reading Recovery, in particular. Reading Recovery teachers have prompts to give and procedures to teach, many of which look similar or appear to be interchangeable, especially if the purpose is not clear. As Noel Jones says in “What’s the Word?” (JRR 6.1, 2006): “Deciding what to say and when to say it is the hardest part of teaching.”

In their training classes, teacher leaders are often asked, “What should I do when…?” Or sometimes jokingly and often in frustration, a teacher says, “Why doesn’t the book just tell me what to do?” Teachers learn early on in the training year, “Children experiencing literacy difficulties do not follow predictable paths of progress. So each lesson sequence will be different for each child. If a teacher expects a child to learn this before that she is forcing a child to move through her notion of sequence in which change must occur. Reading and writing are too complex for that to happen.” (2016, 2)

Different paths

Teachers are like tour guides. They set their destination, where they want their students to be at the end of the year, and generally have an idea of how to guide the students there, assuming they all start in the same place. For the students who are behind or ahead of the starting point, teachers are less certain what to do, but they still try to keep the students on the same path as their classmates. Clay explicitly says that Reading Recovery students will need different paths. “The ideal lesson series will have activities individually selected to meet the needs of a particular child. A Reading Recovery teacher must be very familiar with possible teaching alternatives so that she is able to make good choices moment by moment during each lesson… She will have to free herself from set sequences and vary her teaching to meet the particular needs of children who are struggling.” (2016, 25)

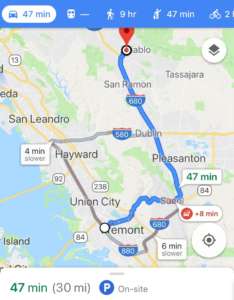

How do teachers do it? Clay writes: “Using observation of what the child can already do and is at present trying to do, the sensitive teacher can interact with these activities taking the child towards the prescribed curriculum not via arbitrary exercises but through activities that are meaningful and enjoyable. This teacher must know all the possible routes to the end goal…”(2015a, 286) and “…must be bold in negotiating shortcuts.“(2016, 25)

With this directive, teachers know what to do: plot out their path, taking the route with the fewest bumps, even though it may not be the shortest or the quickest or the most traveled path to their destination.

Caution

However, this may be tricky. Just like the easy to confuse streets and plazas in Florence, teachers may misread a child’s behavior. “We need to be tentative and flexible because we could be wrong in our explanations from time to time, or from this child to that child.” (2016, 6) Clay explains why: “…What the observer ‘knows’ about reading and writing will determine what that observer is likely to observe in children’s literacy development. You bring to the observation what you already believe. Observers must be aware of this and try to correct for it.” (2013, 12) Even if teachers think they have a plan, “the teaching may have to go the child’s way to the teacher’s goals.” (2015a, 286)

When I mentioned to my daughter that I was thinking about this idea of navigation, she asked, “Should I have done a better job of telling you where we were going?”

Me: No, that was my job.

H: But if I were the teacher and you were the student?

Me: Yes, in that sense, then yeah.

Upon reflection, it isn’t just the teacher’s job. I should have participated more in the journey, at least if I wanted to be independent in getting around Florence. There is a tension between leading and guiding. Noel Jones’ suggestion in What’s the word? is to share the task: “Effective teacher decision-making depends upon careful and sensitive observation during teaching and also upon careful and thoughtful analysis of records after teaching. This is hard work; and what is hard is always easier if the task is shared with someone else… The discussion needs to center on how the child appears to be able to use information from all sources and how he seems to be changing over time in his ability to do this. These discussions can also help teachers improve their abilities in recording and interpreting lesson records and running records.” It is easy to go on autopilot in teaching, doing what has always been done. Instead, teachers may need to do a traffic check before working with the hardest to teach students, similar to driving during rush hour, by conferring with Reading Recovery’s Google maps, aka Literacy Lessons, or with colleagues to ensure that they’re accelerating along the fastest and smoothest route to their destination.

Sandy Brumbaum is a Reading Recovery teacher leader from San Francisco, California.

Any views or claims expressed in The Reading Recovery Connections Blog are those of individual authors, not RRCNA.

THE JOURNAL OF READING RECOVERY

Spring 2024

Constructing a More Complex Neural Network for Working on Written Language That Learns to Extend Itself by Carol A. Lyons

Reading Recovery IS the Science(s) of Reading and the Art of Teaching by Debra Semm Rich

Predictions of Progress: Charting, Adjusting, and Shaping Individual Lessons by Janice Van Dyke and Melissa Wilde

Teachers Designing for Context: Using Integrity Principles to Design Early Literacy Support in Aotearoa New Zealand by Rebecca Jesson, Judy Aitken, and Yu Liu