Teaching Literacy in a Virtual World

by Kathleen A. Brown

Three words come to mind as I think about my experiences and the experiences of my colleagues during this extraordinary time: Resilience, Reflection, and Resetting.

Resilience

Resilience defined by Merriam Webster is an ability to recover from or adjust easily to misfortune or change. The Reading Recovery teachers in my district went from conducting lessons in a school setting to virtual lessons in a matter of a week. Overnight, they had to re-imagine how to provide literacy support to their students in a virtual world. Feet first and with big hearts they jumped into the work. Although there was a steep learning curve with using technology to provide literacy support, collaboratively they worked around the clock to reach the most needy and vulnerable, our Reading Recovery students and their families. While we understood that these were literacy support not traditional one on one lessons, we worked collaboratively with our University Training Center at Saint Mary’s College of California for direction and guidance.

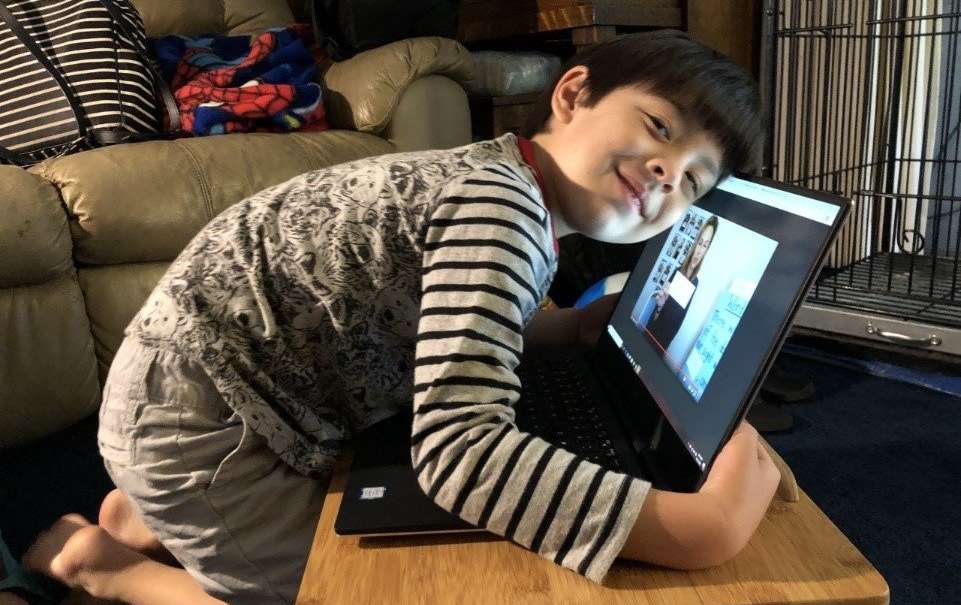

Fortunately, our district provided laptops to all students to participate in online learning opportunities. The Reading Recovery teachers went above and beyond to ensure families had access to the internet and provided countless hours of support in getting families set up for distance learning. In addition, literacy materials were picked up at school sites, mailed home, or delivered directly to the students’ homes. We fondly called the delivery to a home a “Teacher Dash.” Students and their families were so grateful and appreciative of the efforts being made to keep literacy learning going. Teachers were also thrilled to connect with students again, even if it had to be done virtually.

The sudden school closures lead to a range of emotions for our students, their families, and our teachers. Teachers often felt uncomfortable, stressed, and unsure about teaching using technology. There were days of frustration and tears. There were also days of gratitude and celebration as things were coming together and lessons were running much smoother.

Through the ups and downs, high and lows, laughter and tears, we have become stronger and more resilient as teachers and as a collective group. Like our students, we have learned to push the boundaries of our own knowledge and learning to provide literacy support in a virtual world. As one Reading Recovery student said during a literacy support lesson, “I am happy you are still helping me with my reading. When I see you for real, I am going to give you a giant hug.”

Reflection

Reflection is a common practice in Reading Recovery. Therefore, it was not out of the ordinary when my teachers and I started reflecting on our teaching and student engagement during online learning. As defined by Merriam Webster, reflection is a thought, idea, or opinion formed or a remark made as a result of meditation. We continued to meet as a group of Reading Recovery educators to refine our theory and practice related to early literacy teaching and learning. In our virtual on-going professional development sessions, many AHA moments surfaced, which caused us to step back and rethink our interactions with students, our expectations, and preconceived notions about student learning.

We discovered our students are more resilient and independent than we thought. To start with, students adjusted to being at home and away from their teachers and friends, and that was hard. Next, students quickly learned how to use technology, the language of technology, and be prepared to be on time and online for daily literacy support lessons. It is amazing to think we are talking about first graders.

Our relationships with students and their families have changed for the better. Parents have become true partners in this new method of teaching and learning. Beyond the academics, parents opened up about their worries and struggles. As teachers we became a conduit of information, support, and comfort. Having a virtual window into our students and their lives opened our eyes to see them differently and to appreciate those differences.

Reading

Collectively we noticed that students were able to orient themselves to new texts with minimal teacher support. Students were not afraid to pick up a new book or try one out digitally. This is what Marie Clay meant when she stated, “Acceleration is achieved as the child takes over the learning process and works independently, discovering new things for himself inside and outside the lessons.” Literacy Lessons Designed for Individuals, page 20. Students were also demonstrating a variety of ways to figure out unknown words on their own, without teacher prompting or demonstration. “The aim is to have him know about how words work and be able to use this awareness while reading and while writing.” Literacy Lessons Designed for Individuals, page 155. We were astonished by our student’s independence and risk taking while reading novel texts.

Writing

Another discovery is how much more independent students are in writing in a virtual setting. Due to the mere fact there is a screen between the teacher and student, we were not able to physically get in their way, over-scaffold, or be overly involved in the construction of the story. Students were taking more risks in solving new words, not waiting for the teacher to tell them how to solve the words, and writing in longer phrases. These observations mirror what Marie Clay said about students when they become more independent in writing. “Towards the end of the lesson series children will usually be composing on the run, probably writing one sentence, then composing another and writing it, and so on, much the way they would work in the classroom.” Literacy Lessons Designed for Individuals, page 82

Listening and Speaking

Children are naturally social, and learning is a social experience. During daily literacy support lessons, students were overflowing with things to say and share with us. We were a captive audience peering at the screen and listening to language spill out.

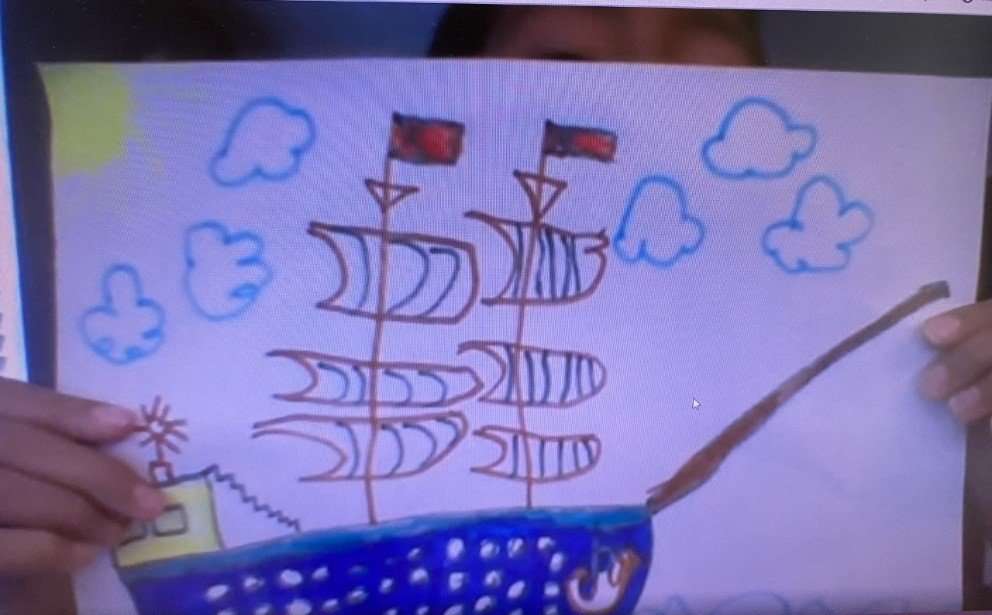

One day, a student I was teaching came with an object to show me and tell me about. This soon became a daily routine. He especially liked showing me and talking about his Lego creations. He was particularly fond of his pirate ship, “The Black Pearl.” From our conversations, he used words like cannons, mast, swords, curse, battle, captain, sailors, etc. Our elaborate conversations turned into descriptive and complex stories. Although I was the teacher (captain), I let my student (pirate) take me on a journey that led to grand conversations and complex written stories, which in turn became his favorite stories to read. I noticed once I loosened up on the wheel, put my own agenda aside, and followed the child, it was smooth sailing.

“Just as a listener tunes in to a speaker, so a teacher must observe, listen to and tune in to a learner. Being sensitive to the child’s thinking allows the teacher to draw his attention to many things. Create opportunities for him to talk and to talk more. Any child with limited language skills needs more opportunities to talk.” Literacy Lessons Designed for Individuals, page 31.

As we all eagerly await the day when we can sit next to our students again, we have learned many lessons along the way:

- Children are more independent than we think they are.

- Children easily adapt to new situations and learning settings.

- Children are pushing the boundaries of their learning in a virtual world

- As teachers, we have a better understanding and appreciation for students, their families, and their life outside of school.

- As teachers, we have learned to find a way to reach our students, no matter what the path or method.

- As teachers we have learned to rely on each other and build upon each other’s strengths.

- As teachers, we have learned to step back, observe more, and wait an extra second or two before intervening or providing scaffolding.

These lessons learned will inform our teaching just as the lessons we had taught previously informed our virtual instruction.

Resetting

Moving forward, we are trying to envision what teaching will be like in the Fall. Will we be sitting next to our students or looking at them through the computer screen? Putting that aside, how will we take the lessons learned during this unprecedented time of teaching and learning and fold them into our daily practice.

Merriam Webster defines resetting as to set again or anew. We must not forget what we have learned about our students, their families, and ourselves as teachers. How do we harness this new learning when we return to our school buildings? The Aha moments are significant. They serve as a catalyst in changing our mindset about student learning and how we teach our students.

Marie Clay asks us to think about change over time in our work with students. On page 44 of Literacy Lessons Designed for Individuals, she states, “To encourage teachers to think about the changes they need to make in their teaching – adjusting expectations and interactions over time according to the progress of each learner.”

As we reset or renew our commitment to teaching our readers and writers, who struggle the most, let us not forget what the children have taught us during this unusual time in our careers and education. Reading Recovery teachers are uniquely positioned to think through what we are learning while learning from this virtual world of teaching. Let us continue to be resilient, reflective, and reset when necessary for our most precious gift: our children, our future.

Kathleen A. Brown has worked in the field of education for 35 years as a teacher, literacy specialist, and Reading Recovery teacher; serving as the Reading Recovery teacher leader in Long Beach Unified School District for the last 20 years. She provides early literacy training for the district and serves on a variety of early intervention / early literacy committees.