What is your song?

by Kim Reynolds

Have you ever heard a song from the past that brings you right back to that very moment in time as if nothing has ever changed? I used to laugh at my parents as an “oldie but goodie” came on the radio causing them to embarrassingly break out into song. This would often lead to stories from their past, some of which brought laughter and others that brought tears. Every time I hear Night Fever by the Bee Gees, I remember sitting on the couch in the living room with my sister watching my parents practice their disco dancing. Yes…they took disco lessons!!! I bet you have found yourself reminiscing about a memorable time in your life as a song quickly takes you back in time.

I now find myself doing the same thing with my own kids. I start obnoxiously singing a Whitney Houston or Laura Branigan song that I hear playing in the middle of Target, which often leads to them conveniently losing me in the store. I love using music to “pump up” before a tough meeting or to “wind down” after a challenging day! Music can also be a great way to accompany a much-needed therapeutic cry, which has happened more than normal this year. I have even cleverly set up my playlist to motivate my way through what I think will be an amazing workout on that daunting treadmill. The music makes me feel like I can successfully run a marathon…even it is for only 15 minutes.

This brings me to our recent Reading Recovery/Literacy Lessons training class graduation celebration. I have a tradition that I pair music to each teacher based on a funny memory, a challenging experience, or a successful moment. This unexpected part of the evening is not on the agenda and catches everyone by surprise, which makes it even more fun when I break out into song with my well-planned playlist.

It has been a challenging year in teaching, but my colleague, Leslie McBane, and I were able to overcome many obstacles that were out of our control to be able to successfully train our teachers. As always, I found comfort in Clay’s words, “The intent is not to find an excuse for the lack of progress, or a label to explain the child’s difficulty, or to state what was thought to be wrong with the child’s past experience at home or at school. The intent is to find a way to get around the roadblock and establish or re-establish accelerated learning.” (Clay, 2016, p. 168). The roadblock that Clay referenced was a doozie this year!! It was rough going, but we did it!!

I made it my goal to find the music to represent this unforgettable time in our lives during our recent end-of-year celebration. You can reminisce with me while I take you through my playlist. Cue in the Jaws theme song. As we began our journey this year, we weren’t sure what to anticipate. There was a lot of uncertainty and tentativeness heading into murky waters. Kelly Clarkson’s Stronger helped us to face the fantastic amount of learning, teach the most challenging students during a pandemic, and balance life in general with tremendous strength.

This brought me to Human by Christina Perri. As we managed to have school visits (remotely and in-person), teach Behind The Glass lessons via Google Meet, and instruct our students with face masks while maintaining social distance, we all came to realize that we are only human. I wanted the teachers to realize that we have survived amazing odds and we need to celebrate. This leads us to Pharrell Williams’s upbeat song Happy. The teachers’ positive energy, willingness to take on new learning, and flexible attitudes have been essential this year. We can clap and be happy together.

At the end of my crazy introduction, I played a song with a memory from this year for each teacher accompanied by my great dance moves! The teachers have overcome many challenges personally and professionally. Luckily the tears and laughter helped us to find a unique perspective and a common experience that will keep our professional and personal bond strong for many years to come.

I used music to make my way through the teaching and learning challenges and newfound opportunities of the pandemic. I drove through the roadblocks that Clay referenced with my playlist in hand trying not to hit the potholes of everyday life. I hope you find your song as I cue in mine… Life is a Highway by Rascal Flatts. I know that we can find our way together even when the pavement is a little rough. I’ll bring the disco ball.

Congratulations to the latest graduates of the Reading Recovery/Literacy Lessons (year 1) teacher training program at The Ohio State University. Pictured above are (back row, left to right) Reading Recovery Teacher Leader Leslie McBane, Kim Myers, Tricia Kucinic, Taylor Kiehl, Melissa Cottrill, Reading Recovery Teacher Leader, Kim Reynolds, and (front row, left to right) Renee Klein, Brittany Maynard, & Cheryl Grimm.

Kim Reynolds is a Reading Recovery Teacher Leader with Dublin City Schools in Dublin, Ohio. She is also the Reading Recovery and Literacy Lessons Docent, The Ohio State University, and a LitCon presenter.

Nawal Qarooni Casiano

Nawal Qarooni Casiano

In class, we recently talked about the importance of representation in the curriculum and focused on Dr. Rudine Sims-Bishop’s work around

In class, we recently talked about the importance of representation in the curriculum and focused on Dr. Rudine Sims-Bishop’s work around

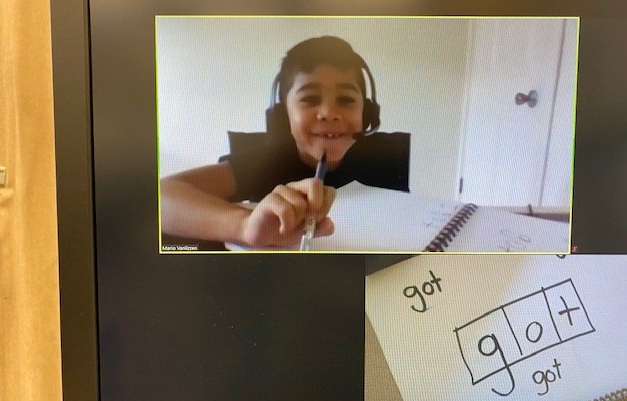

Children are resilient and what they bring to our classrooms, in person or virtually, needs to be acknowledged, valued, respected, and honored. I cannot help but think of Marie Clays’ words of wisdom that remind us that students take different paths to common outcomes and that is both okay and important to take into consideration in instruction. Cassi Clausen reminds us “Ask any child development expert, and they will tell you that children do not develop in a straight line. There are no average children. There are no standard children.”

Children are resilient and what they bring to our classrooms, in person or virtually, needs to be acknowledged, valued, respected, and honored. I cannot help but think of Marie Clays’ words of wisdom that remind us that students take different paths to common outcomes and that is both okay and important to take into consideration in instruction. Cassi Clausen reminds us “Ask any child development expert, and they will tell you that children do not develop in a straight line. There are no average children. There are no standard children.” I have some concern students will be set up for more learning loss if we treat students the same, think they ALL have a loss of learning and we teach to the floor and not the ceiling. As educators, we must have the mindset of acceleration, not remediation, value our student’s new knowledge and experiences, and fill in the gaps when necessary. As Marie Clay has stated in “Literacy Lessons” page 20, “Achieving acceleration is not easy but it must be constantly borne in mind.” Moving forward, ongoing keen observation, formative assessments, and differentiation will be more important than ever. And we must celebrate individual differences as assets. We approach student learning to start where each child is and take them as far as we can. During Mary Howard’s presentation at LitCon 2021, she challenged educators to think about interventions as opportunities throughout the entire school day, not as an isolated act or time. She also expressed interventions should not work in isolation but be connected to a comprehensive learning system. This vision for intervention would be inclusive for all students in need.

I have some concern students will be set up for more learning loss if we treat students the same, think they ALL have a loss of learning and we teach to the floor and not the ceiling. As educators, we must have the mindset of acceleration, not remediation, value our student’s new knowledge and experiences, and fill in the gaps when necessary. As Marie Clay has stated in “Literacy Lessons” page 20, “Achieving acceleration is not easy but it must be constantly borne in mind.” Moving forward, ongoing keen observation, formative assessments, and differentiation will be more important than ever. And we must celebrate individual differences as assets. We approach student learning to start where each child is and take them as far as we can. During Mary Howard’s presentation at LitCon 2021, she challenged educators to think about interventions as opportunities throughout the entire school day, not as an isolated act or time. She also expressed interventions should not work in isolation but be connected to a comprehensive learning system. This vision for intervention would be inclusive for all students in need.