Tell Me a Story

by Connie Dierking

This time of year I am reminded of my grandmother’s large oval dining room table. I see my sisters, brother, mom and dad seated at this table, grandma and grandpa at each end. I can still smell the turkey, homemade noodles and pumpkin pie. I feel the warmth of the oven that has been working overtime. I see the cornucopia salt and pepper shakers tucked between the platters. But mostly … I hear the stories. My family sat at the table for hours retelling the stories of my people. As a child, I grew restless hearing the same stories over and over but I stayed at the table and I listened and I learned. I learned of my parent’s courtship, my dad’s first car, my grandmother’s broken arm, and more embarrassing stories of my childhood than I wanted to hear. I learned the meaning of story. I know now, as a parent and a teacher, that I was one of the lucky ones. My life was couched in story. These were the stories that shaped me then and continue to shape me years later.

The Atlantic Monthly writer, Elaine Reese wrote in her article, What Kids Learn From Hearing Family Stories, “Family stories can be told nearly anywhere. They cost us only our time, our memories, our creativity. They can inspire us, protect us, and bind us to others. So be generous with your stories, and be generous in your stories. Remember that your children may have them for a lifetime.”

School can be a wonderful place to support and develop the oral language skills necessary for telling a story, whether children come into our classrooms having had rich family storytelling and literacy experiences or not. In Teaching for Deep Comprehension (2005), Linda Dorn and Carla Soffos note: “Children involved in talk that included retelling an event using language that includes setting, characters, events, and an ending is an important precursor to comprehension. This is quite simply a story. The potential of storytelling through narrative discourse will assist with growing comprehension skills.”

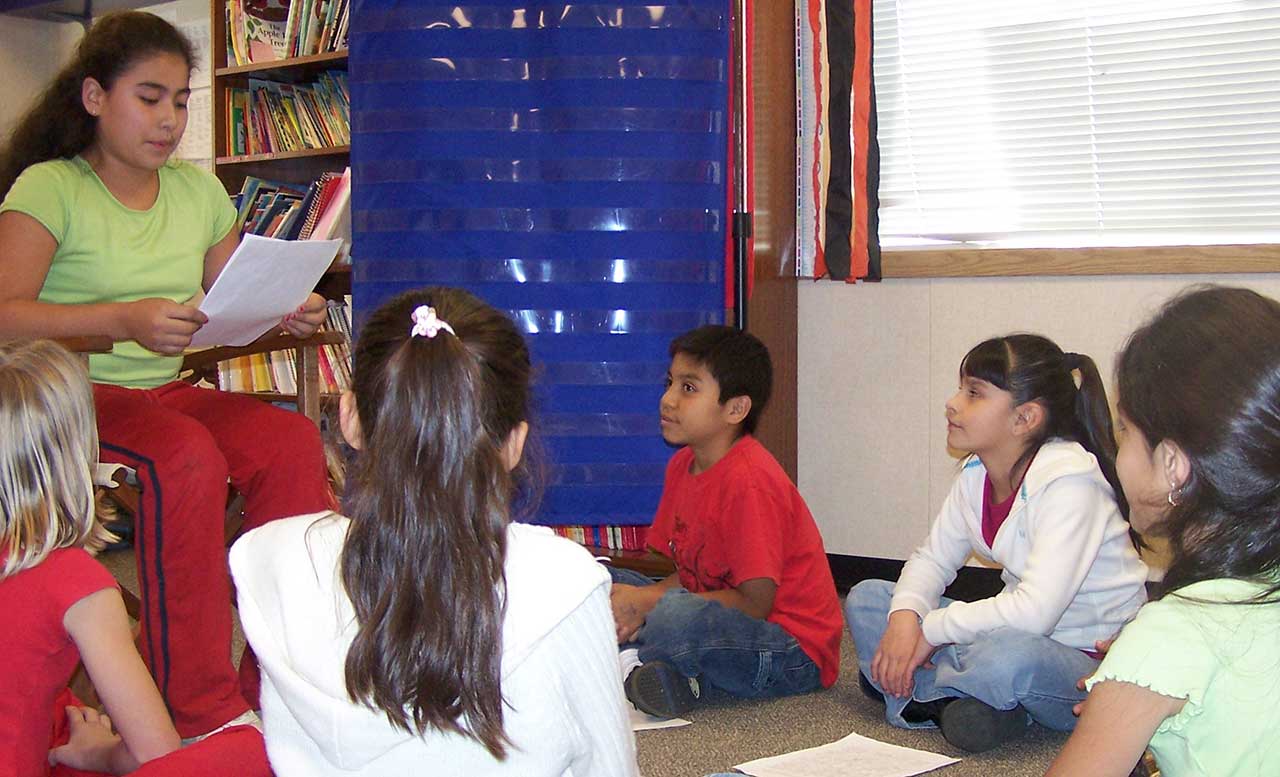

While we can’t sit at the family tables of each student in our classrooms to hear and retell each individual story, we can help our young readers and writers find, hear, and tell the stories of their school lives. We can turn the events of a school day — a lizard on the bookshelf, a water fountain that shoots in the air, an art project, a field trip, or simply the tiny moments that happen any day, at school — into a story.

Finding a shared classroom experience provides the impetus for a class story. Composing that experience in the form of a story that includes a beginning, middle and end, story language, and sentence variety becomes an oral text. When the story is told and retold together, as a class of storytellers, it becomes a tool for practicing the foundation for literacy — oral language. Symbols and gestures support the retelling as students gain fluency and confidence in orally sharing their class story. When Dr. Marie Clay gave her acceptance speech for the National Reading Conference Distinguished Scholar Lifetime Achievement Award, she stated, “I do not study history. I am history.” Our students can become fluent storytellers of their own history. Their oral stories will continue to serve as a text for practicing speaking and listening, reading and writing. A shared story can build a community, provide a structure for telling your own story, and prove that any event can be told in the form of a story.

Example of an oral story on a simple event that happened one day in first grade:

Bubbles, bubbles, bubbles! Today we became…bubble scientists! We each took a bubble wand and blew and blew. Big bubbles, small bubbles, matter of fact all kinds of bubbles filled the air. They looked like iridescent spheres floating through the atmosphere. We studied the bubbles, laughed at the bubbles, and tried not to touch the bubbles. Floating, floating, floating until all of a sudden . . . POP! They disappeared as fast as lightning. Our teacher exclaimed, “I wonder what it would be like to float inside a bubble?”. So we pretended that we could. I guess we will never know for sure. Studying bubbles might be a fun job to have someday. Studying bubbles was buckets of fun.

Connie Dierking is a former primary teacher who has spent over 25 years immersed in the art and science of beginning reading. She is the author of multiple professional books for teachers interested in learning more about the connections between reading, writing, speaking, and listening. She is currently a primary literacy coach providing encouragement and assistance to the teachers in Pinellas County Florida.

Connie will be a speaker at the 2019 National Reading Recovery & K-6 Literacy Conference, February 9-12, in Columbus, OH. Her session is titled “Speaking and Listening: The Forgotten Pieces of the Literary Puzzle.”